[T]he expeditions of Sanbao to the Western Ocean wasted tens of myriads of money and grain, and moreover, the people who met their deaths [on these expeditions] may be counted in the myriads. Although he returned with wonderful precious things, what benefit was it to the state?

Chinese Vice President of the Ministry of War, 1477

When he launched his Jingnan Campaign against the Jianwen Emperor in 1399, Zhu Di knew exactly what he needed: lots of eunuchs.

The Confucian scholar-bureaucrats in Nanjing certainly wouldn’t do. Having long enjoyed imperial favor since the Hongwu Emperor’s accession in 1368, they must have seen little reason to shift their allegiance to an upstart like Zhu Di as long as they kept their status as China’s supreme political advisors.

But such favor came at the expense of the eunuchs, whose power the Hongwu Emperor had reappropriated to the scholar-bureaucrats a generation before. It was the Hongwu Emperor—father to the Jianwen—who had created the Directorate of Ceremonial to, among other things, “supervise eunuch behavior and attire, and scrutinize any eunuch misconduct or violation of palace.” He who had declared that eunuchs would no longer be allowed to communicate with civil officials, all but vanquishing their political power.

Castrate a man once, and he will become a slippery court advisor. Castrate a man twice, and he will go to war. War it would be: as Zhu Di feigned illness to escape the predation of his nephew-turned-emperor, eunuchs joined his ranks in preparation for rebellion. With the latest intelligence from this crafty lot, Zhu Di proceeded to make quick work of the Jianwen Emperor when he finally came out of hiding—by 1402, just three years into the Jingnan Campaign, he had sacked the capital of Nanjing, killed his nephew, and declared himself emperor.

The scholar-bureaucrats would not go so easily, refusing to acknowledge the accession of Zhu Di, now the Yongle Emperor. Very well: the Yongle Emperor purged them and re-established favor with the eunuchs who had paved his road to Nanjing.

It is tempting to wonder how this bureaucratic sea change may have influenced the tenor of rule in China. The eunuchs—composed of Koreans, Jurchens, Mongols, Central Asians, and Vietnamese—were a decidedly more cosmopolitan lot than the stodgy scholar-bureaucrats. Could such a melange have recast China’s position toward the broader world?

It is difficult to say. But not long after the Yongle Emperor’s succession, cosmopolitanism came to the fore when the new emperor commissioned the construction of a fleet—some 300 commodious vessels to hold nearly 28,000 men—for a western voyage. For perhaps the first time in its history, China was putting its unrivaled maritime capacity to global use.

The emperor selected a particularly favored eunuch and mariner, Zheng He, to helm the new ships. A towering man of good stock, Zheng He descended from the Iranian Ajall Shams al-Din Omar, the first provincial governor of the Yunnan province under the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty. The new admiral was just one of many Muslim and Mongol eunuchs who had served the Yongle Emperor since being captured and castrated during the Ming conquest of Yunnan in 1381-2.

As China opened up to the world, Zheng He’s Muslim heritage proved indispensable to diplomacy and trade. Though far from a strict observer himself—more than a few Muslims would probably find fault in worshiping the sea goddess Mazu alongside Allah—Zheng He sponsored the development of mosques throughout Africa and India during his voyages. While in Sri Lanka, he had the Galle Trilingual Inscription erected to honor Allah, Buddha, and Vishnu in their associated tongues (it is uncertain if he maintained a Coexist sticker on the back of his hull as well). Spared from the bigotry of a monotheistic tradition, it seems China may have been especially suited to navigating new worlds with cultural tact.

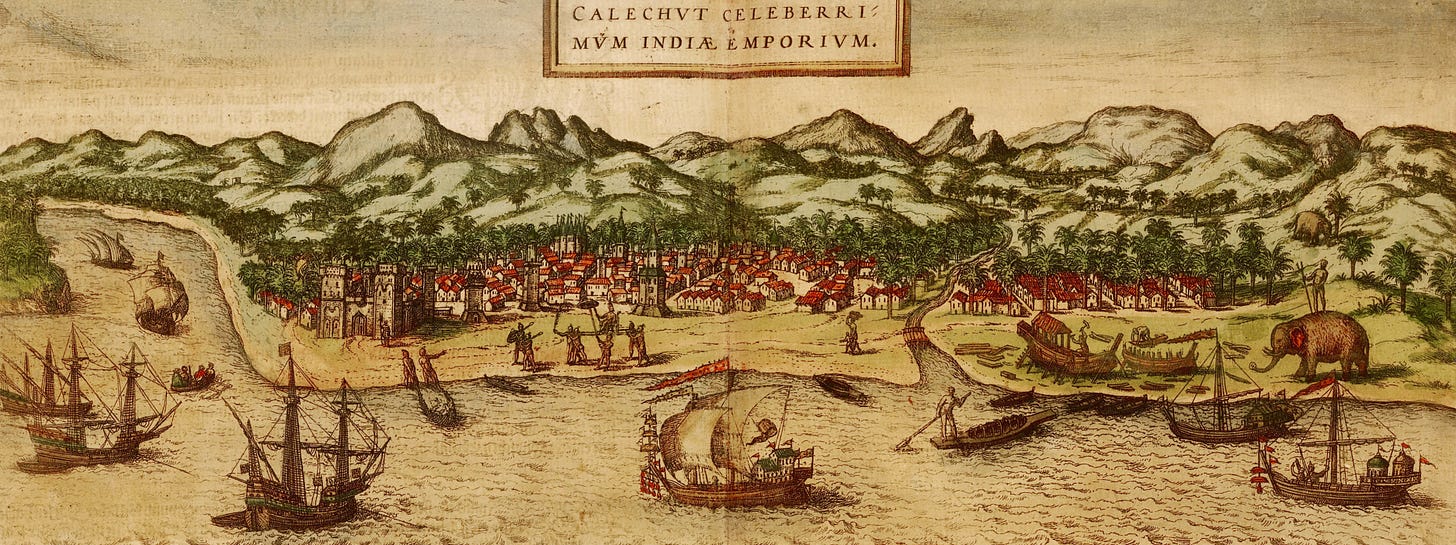

When Zheng He first landed in the Indian town of Calicut, the Muslims who controlled the Zamorin’s lucrative spice trade were thus amenable to his advances. Zheng He would return on each of his subsequent voyages to barter and showcase the Ming Dynasty's might until he died in 1433 and was buried at sea near Calicut.

Such diplomacy eluded Vasco da Gama nearly a century later. After rounding the Cape of Good Hope in 1498 and landing in Calicut, the Portuguese explorer found that the local Muslim merchants had less interest in trading with a Christian whose home country had moved to expel Muslims just a year ago. The best da Gama could do was burn a fleet of Muslims alive while bombarding the city on a return voyage in 1503.

More than da Gama himself, Zheng He was onto something. It was not without friction—just ask the Sinhalese of Sri Lanka, whose king Zheng He helped replace with a Sinophile after the brief Ming–Kotte War—but China was securing new tributaries, bringing in foreign goods, and engaging with new people and ideas, almost a century before Europe entered its own age of exploration.

Of course, China’s opening up to the world, and the promises therein, died with Zheng He, somewhere off the coast of Calicut in a murky grave. The traditional explanation is one of waste and extravagance—putting so many large hulls to sea cost the empire mightily, and the exotic goods (ostriches, elephants, other nonsense) such voyages generated were not enough to finance future ventures.

While the Ming Treasure Voyages were no cut-rate undertaking, budgetary constraints were not likely the cause of their cessation. For one, it must have been easy to see that a host of new trading partners was already enriching China. The ample cobalt oxide purchased in Persia, for example, was enough to sustain China’s porcelain industry for decades to come.

More likely, the story is one of special interests. State-sponsored foreign trade was anathema to China’s private merchants who had little interest in competing with imperial excursions into a global market. After the death of both Zheng He and the Yongle Emperor, private lobbying against seafaring expeditions apparently won out in the new capital of Beijing.

There was also the waning of eunuch influence in the imperial court. While the eunuchs had spearheaded outward expansion under the Yongle Emperor, the diminished scholar-bureaucrats found the growing concentration of fiscal power with the emperor and his castrated coterie an unwelcome development. With the accession of the eight-year-old Zhengtong Emperor in 1435, the scholar-bureaucrats had their chance to reassert fiscal power. The first step was to suspend the extravagant voyages, which were financed unilaterally by the emperor.

Budgets or bureaucrats—never mind the precise details. In 1435, seven voyages into the venture, China quashed its global ambitions. Export goods were banned, key naval offices shuttered, and the unsurpassed hulls that had come to control the Indian Ocean dismantled. By 1500, it would be a capital offense just to build a ship with more than two masts. Remarkably, China did not just suspend support for exploration, but actively crippled its maritime capacity.

In an age when man funds lunar voyages to poke at rocks, it is strange to think that one of the world’s largest empires six centuries ago decided that a bevy of new tributaries and trade partners just wasn’t worth it.

Of course, the Ming Treasure Voyages were just one episode in China’s tradition of false starts.

The scholar-bureaucrats, keepers of Confucian harmony above all, long detested anything that sniffed of commercial dynamism. This manifested not just in the autarkic impulse that sank the Ming Treasure Voyages, but in a rejection of technology more generally. China did not lack ideas—it had invented movable type, gunpowder, and iron smelting well before Europe—but under a centralized bureaucracy that preferred constancy, such innovations could not have the same disruptive impact—good and bad—they would in Europe.

Plenty of European rulers were equally suspicious of technology and change. Suetonius tells us that Emperor Vespasian rejected an engineer’s offer to help move columns more efficiently out of fear that it would dispense with the back-breaking labor that made up Roman wages:

How will it be possible for me to feed the populace? You must allow my poor hauliers to earn their bread

But the kind of power Vespasian wielded would not last in Europe. As Walter Scheidel shows in his very good Escape from Rome, after that great Decline and Fall, no one ruler or bureaucracy could sustain such a monopoly of continent-wide power.

Fragmentation reintroduced the interstate competition of classical Greece (by no coincidence a much wealthier society than Rome), making it especially difficult to suppress any one innovation, idea, or even people at the continental level.

By the age of exploration, just as in China, plenty of European rulers were trying their best to derail commerce—but it was harder to coordinate at a continental scale. When Portuguese and Spanish Catholicism reached a bloody crescendo, Jews, along with their commercial knowledge, flocked to the Low Countries, where they helped catalyze the Dutch into their own Golden Age as Spain and Portugal slipped into a mercantile siesta.

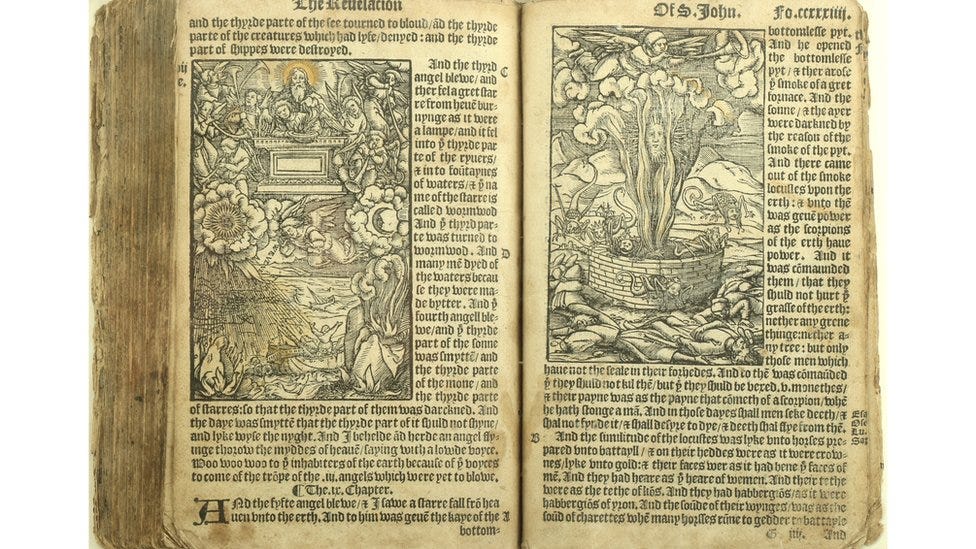

Ideas, like people, could not be so easily controlled. When Tyndale decided in the early 16th century to introduce an English Bible for commoners, the Anglican Church would have none of it. However, the Anglican Church did not govern all of Europe, and Tyndale quickly moved to Antwerp, where he could print his first edition copies in 1526 to smuggle back into England.

Personal Bibles proved a big hit. While the Anglican Church finally succeeded in arresting and executing Tyndale, English Bibles, and the very concept of reading the Bible oneself, had already spread, making continued censorship hopeless. Very well: King James relented soon after, commissioning his eponymous version to supplant Tyndale’s illicit copies.

Under such a diffused power structure, cats tended to stray from bags. Jewish commerce, Tyndale’s Bible—freed from the whims of a single continent-spanning bureaucracy as in China, ideas, people, and goods had a better chance of finding a niche.

Perhaps for the first time since the Roman Empire, the rules and regulations of a single government known as the “European Union” stretch across the European continent. To be sure, a semblance of national sovereignty is retained for constituent states, but only for the most humdrum matters. Markets, the stuff that builds civilizations, are decidedly common.

None of this is inexplicable or without benefit. An integrated market militates against continent-razing wars. It streamlines corporate compliance and trade to the benefit of everyone.

But what the EU represents increasingly dispenses with what Europe once was, and indeed, it feels much more Ming than Roman.

Rome, remember, was an unlikely empire. How did it scale up in such a divided continent? In its earliest days, it was something of a militaristic Ponzi scheme—conquer a state, share its plunder with the legionaries, and promise new captives that they could enjoy their share of loot if they helped conquer the next town over. Rinse and repeat.

But things were too tenuous for Rome to care so much about how its new subjects conducted their internal affairs—small tributes were required, but governance had to be devolved largely to the existing state. The Samnites could keep doing their thing, more or less, and Rome could not control the far-flung reaches of its empire with more than a very light touch.

The EU, too, was born of militarism —but unlike in Rome, it was an aversion to the bloodshed therein that pushed modern Europeans toward a centralized power structure. Two contrasting models for two different epochs: join the Roman Legion and you can have glory and plunder; join the EU and you can enjoy security and bureaucracy.

That foundational principle—to uphold continental harmony—has shaped the EU’s governance more along the lines of the Ming scholar-bureaucrats than Roman militarists. Given the ominous backdrop—two world wars and millions of lives wasted—the EU’s bureaucrats must always be active and assertive, honing in on the latest threats to social harmony. Just imagine the alternative.

But facing little threat from actual bloodshed in recent years, the EU’s regulators have, like true Ming scholar-bureaucrats, turned their aims toward commercial activities—none more than those in tech.

So far, the EU’s regulators have succeeded in stifling tech companies more than the actual Confucians: just four of the world’s 50 largest tech companies belong to Europe, compared to eight for East Asia. Japan claims more behemoths than any single European nation.

How does the EU do it? In no small part by being an innovator in regulating innovation. Among its recent triumphs is the General Data Protection Regulation, implemented in 2018. Besides being impossibly complex to enforce, a recent study estimated it reduced both EU user website page views and website revenue by 12%. Such is the price of the latest entry on that growing list of human rights—to be forgotten.

It would be a mistake to see this as a one-off. The EU is now gearing up to be the first to contain artificial intelligence, reaching an agreement on the latest iteration of its trailblazing AI Act just days ago.

What does this sprawling 900-page law entail? Among other things, it creates a hierarchy of risk for AI use cases, ranging from “unacceptable” to “minimal.”

Unacceptable use cases—those that will be banned from the start—include:

Cognitive behavioural manipulation of people or specific vulnerable groups: for example voice-activated toys that encourage dangerous behaviour in children

Social scoring: classifying people based on behaviour, socio-economic status or personal characteristics

Biometric identification and categorisation of people

Real-time and remote biometric identification systems, such as facial recognition

The last of these is already the basis for an American company, Clearview AI. Too Black Mirror for most!

What about high-risk use cases that must meet a host of compliance standards before hitting the market? Here, it seems the EU went big (and vague):

EU-regulated safety products like toys and medical devices

Management and operation of critical infrastructure

Education and vocational training (meaning access and assessment)

Employment, worker management and access to self-employment

Access to and enjoyment of essential private services and public services and benefits

Law enforcement

Migration, asylum and border control management

Assistance in legal interpretation and application of the law.

Assistance in legal interpretation? High risk? Sounds like all the aspiring BigLaw associates out there should start learning French.

On top of all this, developers of generative AI tools like ChatGPT will have to disclose to Europe’s brand new “AI Office” how their models work, publicize training data, and ensure compliance with copyright laws. (Update for future lawyers: learn French and intellectual property law.)

Never mind that there are no European AI giants to even reign in—innovation is for lawyers. Sure, the French Mistral AI shows promise, but it still lags behind its American counterparts. Is it going to leapfrog America’s best with regulatory watchdogs and French labor laws looming?

Maybe this is all very sensible. Maybe none of the EU’s restrictions will hinder new ventures, and maybe none of the banned applications will ever find ethical use. Maybe I will be enjoying French AI tools twenty years from now with my sour grapes.

But as the EU moves to contain AI before most of its potential is even understood, it is worth taking the long view. Nearly all of Europe is now subject to the rulemaking of a bureaucracy that has in its short history erred on the side of excessive caution concerning technology. In that short period, tech has mostly passed Europe by, concentrating in the US, whose GDP continues to diverge from Europe’s. If we are in an age of digital exploration, it seems that the EU, much like the Ming bureaucracy, is laboring to restrain its people from the farther reaches of this new world.

Should we fear then that 500 years from now, historians will look back at the present moment, and convincingly explain how Europe’s centralized bureaucracy, paired with a culture of risk aversion, undermined its adoption of world-changing technology? Will the post-mortem after a third divergence tell how Europe, not unlike its eastern neighbor generations before, preferred social harmony to change?

We live in a globalized world—Europe cannot lag so far behind its commercial superiors as long as its institutions can keep the lights on. But globalization also means Europe’s exit from the world of technological disruption is not as self-contained as China’s tradition of stagnant autarky. The EU’s regulators write rules with a global audience in mind, hoping that the “Brussels effect” will shape the world in Europe’s own sterilized image. Europe has combined China’s historic loathing of technological disruption with outward ambition.

The results remain to be seen, but for the moment, Brexit looks all the more valuable. The UK, despite its recent malaise, maintains the promise of reviving itself as a hub of industry. Under Rishi Sunak it has made strides in positioning itself as a more tech-positive alternative to its continental neighbors. Still, those hopes are far from being realized. Europe—once the place of labs, workshops, and trading floors—looks more like a museum with each passing day.

Until the UK learns how to build again, most specifically housing, she will never be anything more than a stagnant backwater.

Dan Wang said it best: the UK is in the “sound clever” business, as opposed to the innovation and research business.

Good luck