This past fall, I visited Japan for the first time. It was a less than ideal time for a trip, with Tokyo and Kyoto both experiencing a particularly humid heat wave and an influx of tourists (seeing a temple in Kyoto has this kind of waiting-in-line-at-Disney-World feeling, I’m sad to report), but I was interested to see how Tokyo differed from Seoul and Busan, my home turf for the six months prior. And in particular, I was curious as to how these difference might explain the gap between Japan and South Korea’s fertility rates (1.2 and 0.68, respectively).

Immediately, I was struck by how much more family friendly Tokyo felt than Seoul or Busan. When I walked off the beaten trail and down side streets in Tokyo, I often found myself alone in areas that seemed residential. (It seemed like the same maneuver in Seoul or Busan usually led me to older men taking their smoke breaks.) Tokyo could be crowded, but it also felt like it had the potential to be much more spacious.

Surprisingly, Greater Tokyo’s 43 million people per 13,500 km2 registers as even denser than the Seoul Capital Area’s 26 million residents per 12,685 km2. But these figures are misleading. If you know anything about the topography of these cities, you know Seoul is extremely mountainous, while Tokyo is flat. In turn, Tokyo has a lot more low-rises than Seoul. Look at these satellite images of Tokyo and Seoul at night:

Tokyo is on an alluvial plane that enables horizontal development, while Seoul’s urban areas have congealed around mountain summits. (Busan seems subject to the same problem, and indeed space is so limited that the public schools were built in the mountains, which makes for a hellish commute but also great VO2 max training.) By some other measures, the Seoul metro really is the densest metro in the OECD, with three times the density of Greater Tokyo, though I’m not sure what exact adjustments were made to generate this figure.

How the Seoul and Tokyo metro areas are administered is equally telling. Seoul’s metro area is defined in just three parts—the city of Seoul, the city of Incheon, and Gyeonggi Province. The last of these makes up 10,184 km2 of the Seoul metro’s 12,685 km2 area. This means the cities of Seoul and Incheon together are only about 15 percent of the Seoul Capital Area but comprise half of the population. The rest is administered as a province with a long list of satellite cities.

Tokyo’s subdivisions are much more extensive—and confusing. In addition to the Tokyo Metropolis —which itself contains 23 special wards (Tokyo’s original core) and 26 cities—there are the prefectures of Chiba, Gunma, Ibaraki, Kanagawa, Saitama, and Tochigi, encompassing their own long list of suburban cities. In effect, Greater Tokyo is seven different prefectures, with lots of cities abutting each other. Such administration reflects relatively seamless horizontal development, adding up to an area similar to the Seoul metro’s (~13,000 km2).

So I think it is reasonable to say Tokyo is a bit flatter, a bit quieter, and maybe a little more family friendly. And data shows Seoul’s fertility rate of 0.55 is much lower than Tokyo’s (0.99). But does Seoul’s density actually matter for fertility rates?

There is meh evidence that density itself is not so good for fertility, but much better evidence that inhabiting cramped apartments or living with your parents into adulthood—as 81 percent of Koreans in their 20s do—is especially detrimental to family formation. Such living arrangements indeed appear to be much more common in Seoul than Tokyo, as the city is much more expensive for locals. A report from the Bank of Korea found that Seoul’s price-to-income ratio stands at 25—far and away above even cities like New York (11). Worryingly, Koreans in their 20s just keep moving into Seoul’s core despite these financial constraints.

So perhaps Seoul’s density is not as big of a problem as the cost-saving living arrangements associated with it. This seems plausible based on the experience of Europe, where Spain and Italy have both some of the highest rates of young adults living with their parents (around the same as South Korea’s rates) and the continent’s lowest fertility rates (around the same as Japan and China’s rates). (The root cause of such arrangements in southern Europe would seem to be a truly terrible labor market rather than density.) Whether young people can afford their own places probably does matter for fertility rates, at least some.

Of course, no South Korean city or province has a fertility rate over 1.0, suggesting affordability is not major direct causes of South Korea’s fertility decline. If those were the true constraints, then people living in rural provinces with low costs of living should have much higher fertility rates than at least Japan, right?

We should remember the unusual gravitational force Seoul has for young Koreans—both physical and cultural. Half of South Korea now lives around the capital, an anomalous level of geographic concentration within the developed world. (For comparison, one-third of Japan lives around Tokyo, but Tokyo is also an unusually affordable city for its size.) Part of that might be peer effects, but part is that Seoul is just the center of everything a young person might care about—chaebol jobs (as I documented earlier this year), education, etc. Young Koreans are responding to real, material incentives.

And even if the costs associated with this regional imbalance are not lowering fertility rates within Seoul, such geographic concentration undoubtedly makes Seoul’s influence on the rest of the country disproportionate relative to other capitals. We should consider, then, that Seoul’s low fertility norms are spreading via social contagion to other parts of the country.

Let’s illustrate this with a simple thought experiment. Imagine the New York City metro area were half of the US. In such a scenario, the median American outside New York City would probably be much more like the median New Yorker. They would consume more media made by New Yorkers, be more likely to have friends and family living in New York, visit New York more often, and be more likely to relocate to New York at some point in their lives. New York, we might imagine, would start to rub off on non-New Yorkers to a much larger degree than it does making up just 6 percent of the US population. And if New York had an extremely low fertility rate—perhaps due to some interaction between values and lived environment—those norms might spread to those outside New York. (Now imagine this scenario with 98 percent of the US made up of a single ethnicity and culture.)

So there could be a kind of vicious cycle at work, where young South Koreans pack into Seoul’s core under conditions that deter family formation, Seoul’s fertility rate decreases due to local values and/or costs of living, and the rest of the country models their behavior on these norms. If half the country is already putting off having kids until their 30s because they live in Seoul, people in even a more affordable city like Busan might come to think it’s premature to get married at 28 (this sentiment was in fact expressed by a teacher I worked with.)

Understanding why half of South Korea lives around a single city—and why Seoul has become so dense and expensive—may thus be important to understanding why South Korea’s fertility is low by even East Asian standards. So let’s trace how Seoul became the crowded center of the Korean world.

The Economics of Population Distribution

Before we consider why Seoul has developed in such a dense way, let’s consider why half of South Korea lives around it in the first place.

To do so, we need to start with an ambitious and not so obvious question: what determines the distribution and size of cities in the first place?

Economists have posited three theories:

increasing returns: different-sized cities develop due to positive feedback loops from knowledge spillovers, labor market pooling, and trade proximity

random growth: distribution of different-sized cities is stochastic (fancy word for random)

location fundamentals: fundamental features such as climate, rivers, etc. of different cities drive growth

Each of these, of course, has some explanatory power. Consider New York City—it benefited from location fundamentals (natural harbor), random historical factors (early immigrant settlement from Europe), and increasing returns (financial hub). No one theory can explain its rise.

But this presents interesting questions about just how much each factor matters. That is a tricky thing to measure, but Donald R. Davis and David E. Weinstein’s paper “The Geography of Economic Activity” is a useful guide, and luckily for us, it concentrates on a country not far from South Korea—Japan.

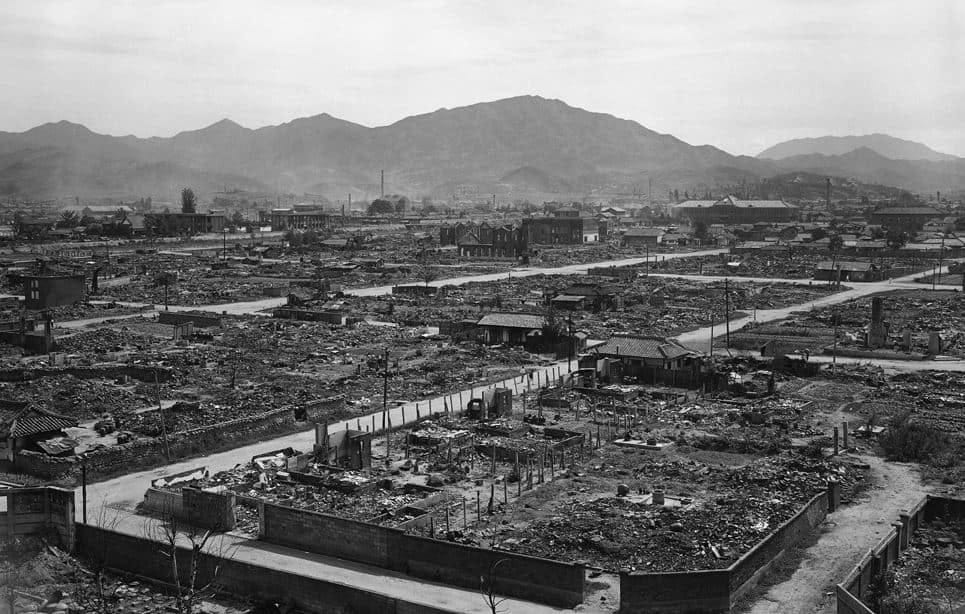

Davis and Weinstein use a clever natural experiment to measure these theories against each other. By looking at population changes in response to allied bombing campaigns of Japan during World War II, they get a good glimpse of just how much location fundamentals matter.

If growth is random, we might expect bombings to dislocate populations permanently. No one will bother to repopulate a city once its destroyed if living there was a matter of chance to begin with. Similarly, if it’s increasing returns that determine your home, then once an area is bombed and agglomeration benefits disappear, populations should just gather in the new areas with the most economic benefits.

But Davis and Weinstein find something interesting—Japanese cities that got blown up during World War II tended to recover their pre-war relative size. People kept moving to places after they had been reduced to ashes.

Of course, that tends to lend a lot of support the idea that location fundamentals play a large role in determining where people live, meaning population distribution is somewhat sticky. Perhaps a city is good for its climate, rivers, or security, and worth recovering even in the event of total annihilation. Or as they put it:

Even very strong temporary shocks have virtually no permanent impact on the relative size of cities.

This isn’t to say that increasing returns don’t matter—Davis and Weinstein find plenty of evidence for those effects, too. Perhaps the fact that Tokyo became such a hub despite its large earthquake risk shows people are willing to defy certain location fundamentals if increasing returns are sufficient.

So Davis and Weinstein develop a hybrid theory of sorts—location fundamentals and increasing returns matter a lot. Random shocks can matter in the short-term—if your city gets razed, say—but perhaps somewhat surprisingly, they typically has little influence over long-term population distribution.

The idea that increasing returns would matter for Seoul’s success is self-evident, but let’s think first about location fundamentals with respect to Korea. If Davis and Weinstein’s maxim holds, we might expect that Korea’s population distribution in the past resembles its distribution today. Is that the case?

Gyeongju

Let’s say you were alive in the 9th century AD. What cities would you be most likely to inhabit? And in keeping with Davis and Weinstein’s research, let’s ask:

Would you be likely to inhabit them today?

We might start with Chang'an, a Chinese commercial hub that once sat along the Silk Road. Chang’an abides by Davis and Weinstein’s maxim. Today, the city is known as Xi’an and sports a massive population of 13 million. Xi’an lost some of its relative size, but it’s still the 10th largest city in China today. (Remember, China has a lot of cities.)

Next, we may consider Baghdad, once the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, and presently the capital of Iraq. Baghdad now sports a population of nearly 10 million and continues to be the largest city in modern Iraq, and the fourth largest in the Middle East. Its relative standing is still strong.

How about Constantinople? Istanbul now has a population of almost 16 million. Even though Ankara is the capital of Turkey today, Istanbul remains among the largest cities in the world. No surprise here.

But on this list of great 9th-century cities comes a surprise: Gyeongju, a commercial hub of early Korea. Though smaller than the cities above, Gyeongju’s estimated population of 200,000 made it among the largest cities in the world in the 9th century. Today, it is not even one of the Korean peninsula’s 20 largest cities, with a population of just 264,000.

If allied bombing campaigns can’t even disrupt population centers in Japan, and if Xi’an, Baghdad, and Istanbul are still among the world’s largest cities, what happened to Gyeongju?

Gyeongju was no fluke. It served as the capital of the Silla Kingdom for over one thousand years. For most of that time, the Silla Kingdom was one of Korea’s three kingdoms, along with Goguryeo and Baekje. That changed when Korea was finally unified under the Great Silla Kingdom from 668 to 935 AD, thanks in large part to intervention by the Tang Dynasty in China. Throughout this period, Gyeongju maintained an outsized population for a simple reason: it was a hub for trade on the Silk Road—just like Xi’an, Baghdad, and Istanbul.

Gyeongju’s fortunes began to turn when Korea’s capital relocated to Kaesong with the arrival of the Goryeo Dynasty. This initial move was probably not such a disaster—Gyeongju seems to have continued to play a role as a leading city during this time, not least because the Goryeo was, like the Silla, a Buddhist dynasty. But after the Goryeo came Korea’s most recent and culturally defining dynasty: the Joseon. Suddenly, Gyeongju was a commercial, Buddhist city in a Neo-Confucian world.

The simple explanation for Gyeongju’s decline is that, just as it despised Buddhism, the Neo-Confucian Joseon dynasty loathed commerce, and the kind of trading networks that defined the Silla Kingdom languished. The pinnacle of virtue for a Joseon Confucian, of course, was memorizing poetry and achieving yangban status. Like many Buddhist relics in the Middle East today, Gyeongju was even subject to attacks from militants throughout the Joseon period—yes, militant Neo-Confucians (these were the same ideologues who came up with foot binding in China, mind you).

Remarkably, no Korean cities surpassed Gyeongju’s population figures during the Joseon Dynasty (1334-1910). If the figures are to be believed, Seoul’s population of about 200,000 in 1910 was similar to the size of 9th-century Gyeongju. Korea had become, as western travelers dubbed it in the 19th century, a “hermit kingdom.”

Of course, other global commercial hubs have failed, too. Consider Cordoba. Today, it is around the same size as Gyeongju, but around the 9th century, it was also among the largest cities in the world. And like Gyeongju, it served as a cultural and commercial hub for an alien religion within its host country—in this case, the Islam of the Umayyads, who had fled to Spain with the arrival of the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad. Yet with the reconquest of southern Spain, Cordoba’s relevance, like Gyeongju’s, faded.

We might say, then, that Gyeongju faced permanent shocks—not mere bombings, but dynastic and religious changes that relegated it to the dustbin of history. And permanent shocks, as you might already suspect, are a theme in Korea’s urban history.

Kaesong and Pyongyang

With the ascension of the Joseon Dynasty, Seoul’s primacy in Korean life was secured. What made South Korea’s present capital such an appealing locale in the 12th century? In part, it aligned with the principles of geomancy. But Seoul also likely appealed for the very terrain that constrains its growth today. A mountainous surrounding made for very good defense against potential invaders, and you can see the city’s remaining fortress wall around downtown today.

As mentioned above, Seoul never surpassed the heights of early Gyeongju during the Joseon period, reflecting a decline in Korea’s commercial activity during the Joseon.

Here is a funny consequence, which Korean nationalists are keen to point out: Japanese introduced prostitution to Korea. But as the scholar Andrei Lankov points out, Japan also introduced a theater and restaurant culture. Prostitution, theater and restaurants are fruits (or not fruits, given your disposition) of urban living, of which Korea had little.

By Lankov’s estimate, Korea had an urbanization rate well below 8 percent in 1789. Seoul, its largest city, still contained fewer than 200,000 people, and the next two largest cities—Kaesong and Pyongyang—were much smaller, with populations of around just 30,000.

Japan, by contrast, had an urbanization rate of some 15 percent during its late Edo period, and Tokyo maintained a population of nearly 1,000,000. Just before the Meiji Restoration in 1873, during which Japan modernized to become Asia’s leading power, cities like Osaka, Kyoto, Kanazawa, and Nagoya already had populations of over 100,000. The parts of China around the low Yangtze River, for their part, enjoyed an urbanization rate of 17 percent.

So in the Joseon Dynasty, Korea was anomalously rural even within pre-industrial East Asia. Still, in keeping with Davis and Weinstein, we might expect the relative importance of its second and third cities—Kaesong and Pyongyang—to persist today.

Of course, these cities, like Gyeongju, faced permanent shocks: both became part of North Korea with the division of the peninsula at the 38th parallel in 1945. It is tempting to wonder: what would have come of Pyongyang and Kaesong in a united Korea?

Given its status as capital of North Korea, Pyongyang remains one of the most significant cities on the Korean peninsula today, yet its population sits at about just 3 million. Pyongyang’s rise as a capital had deep historic roots—the city is associated with Tangun, the mythical founder of the Korean people, and served as the capital of both the Gojoseon and Goguryeo kingdoms. (NB: North Korea insists Tangun is not so mythical based on some bones they dug up, and you can visit his purported mausoleum near Pyongyang today). In the Joseon period, though, Pyongyang developed a reputation as a backwater associated with dissident movements, such as Hong Gyeong-rae's Rebellion of 1811-12. It was similarly a stronghold for Christianity up until the city’s communist turn, and indeed, Kim Il-sung himself was raised by Christian parents.

Despite its declining fortunes in the Joseon, Pyongyang should have become a megacity under normal development conditions. For context, southern Korea was long the breadbasket of the peninsula, maintaining most of the Korean population—around 60-65 percent at the end of the Joseon Dynasty. But northern Korea, being colder and more mountainous, featured large deposits of coal, iron ore, and magnesite—ideal for the development of steel mills and heavy industry. By the end of the Japanese colonial period, the north had already become more developed than the south, and Pyongyang was at the center of an emerging industrial economy. With both strong location fundamentals, and increasing returns, Pyongyang looked poised to become a draw for economic migrants from the the crowded, agrarian south.

Not only did Pyongyang not draw in southerners, but from the division of the peninsula at the 38th parallel in 1945 to the formal founding of North Korea in 1948, around one-third of Koreans in the north migrated south. Only a trivial number of southern Koreans went in the opposite direction (Stalinist terror is a tough sell). And the most convenient city for any northern migrant to settle in would have been the largest one that sits right next to the 38th parallel—Seoul.

Another southern influx came after the armistice in 1953, when displaced Koreans in Japan and Manchuria were repatriated on a massive scale. Again, Soviet-style communism proved a repellent, and about 80 percent of these migrants opted to live in South Korea. The total number of returnees and refugees that entered South Korea was estimated at more than 3 million—about 15 percent of the total South Korean population.

The result of these migration patterns is that, from 1945 to 1955, North Korea’s population declined, while South Korea’s gained over 5 million people. Many who should have been settling in the north amid an industrial boom were instead crowding into Seoul at a time when Korean fertility rates were on par with sub-Saharan Africa. This shock, of course, has been far from temporary.

What about Kaesong? While it was not an emergent industrial base like Pyongyang, its location—it sits just north of the DMZ, less than 60 km from Seoul—invites counterfactual consideration.

Given its proximity to Seoul, Kaesong could have served as a sister city to the southern capital. At the very least, if North Korea had followed a path similar to China and reached a two-systems, one country arrangement, Kaesong might have become the Shenzhen to South Korea’s Hong Kong—a gateway between the two sides of the peninsula.

On a long enough timeline with North Korean catch-up growth, this could have helped alleviate the immense housing costs for young people around Seoul. With free movement between the two sides of Korea—and a good deal of North Korean liberalization—young South Koreans might have been chosen to commute to jobs in Seoul from Kaesong to save on rent. A high-speed rail trip from Kaesong to Seoul would take less than 30 minutes, assuming typical speeds.

Such a scenario was closer to being realized than you might imagine. Under South Korean President Kim Dae-jung’s “sunshine policy” in the early 2000s, both Koreas agreed to create the Kaesong Industrial Region, an industrial park that allowed South Korean businesses to employ North Koreans in manufacturing. This was supposed to be a win-win: North Korea had cheap labor, while South Korea had investor capital and the rule of law. Again, this was not so different than Hong Kong’s relationship with cities like Shenzhen in the 1990s.

Of course, North Korea never opened up like China. Those reasons may never be fully clear, but George Bush’s axis of evil cosmology in which North Korea featured prominently and the invasion of Iraq did little to reassure Kim Jong-il as he considered following China’s path. By the 2010s, military provocations by Kim Jong-il’s son, Kim Jong-un, led to a termination of the agreement between the two Koreas. North Korea remains poor and isolated, and Kaesong—much like Gyeongju—remains a relic.

All Roads Lead to Seoul

Here is another very broad question—why do industries develop in the places they do?

Consider the US. Historically, the automotive industry was located in the Midwest. Why there and not, say, the southeast?

As you might imagine, midwestern cities like Detroit had desirable qualities for a prospective automobile company. There was an abundance of immigrant labor willing to work and proximity to critical resources for building cars, such as steel. All that steel had equally helped develop robust railroad networks to move products around.

And once a company like Ford set up around Detroit, it became more logical for others to do so. General Motors could learn from Ford’s operations, tap into the same pools of labor, and emulate existing supply chains. This is much more seamless than setting up shop across the country and hoping you can efficiently find the right labor, resources, and know-how.

Businesses then, abide largely by the same logic as people—they seek places with strong location fundamentals and increasing returns. And where industries agglomerate is itself tied to where people want to work. Detroit was the fourth largest city in the US at the peak of its automotive industry. All the same, its decline today is closely linked to the demise of companies like Ford and GM.

While no one would celebrate the decline of the American Midwest, the evolving fortunes of different US regions stem in large part from market dynamism—not such a terrible thing. For much of the late 20th century, the US lost its comparative advantage in automotive manufacturing to emergent powers like Japan and South Korea. Simultaneously, new American industries like software soared in the Bay Area. Despite their best efforts, Japan and Korea struggled to compete with the US in this sector.

But imagine an alternate universe in which a single US city became the center of every major industry. Take Detroit—what if Detroit had been the center of American finance, pharmaceuticals, manufacturing, tech, energy, and so on? Under such a scenario, a decline in the automotive industry would have meant little. Not only that, but the premium to living in Detroit would be unusually high, and we might expect that exorbitant numbers of people would try to agglomerate in the Detroit metro area. Whatever your industry, there’s a good chance your career would benefit from living in Detroit—increasing returns would be supercharged. But this might create other negative externalities that outweigh the agglomeration benefits—say, high housing costs, unhealthy pollution levels, cultural homogenization in the direction of low fertility norms.

Of course, this hypothetical is not so far off from reality in South Korea. Seoul today is the center of most major industries in South Korea, from finance to tech to pharmaceuticals.

South Korea is a small country, which may make agglomeration in Seoul more convenient—it takes just some 3 hours on a train to get across the country. But it is possible to have multiple competing economic centers in a small space. Consider Guangzhou and Shenzhen. Along with Beijing and Shanghai, both are regarded as first-tier Chinese cities that stand among the largest urban centers in the world. They are also within two hours of each other. How did Guangzhou and Shenzhen develop to such heights in close proximity? Industry allocation plays a role. Guangzhou, with its longstanding history as a trading post, excels in exports such as textiles and automobiles, while Shenzhen became a center for technology, innovation, and finance thanks to its status as a special economic zone during China’s opening-up period.

The question is—why did almost all major industries agglomerate in Seoul?

South Korea’s unique development model offers an answer. As I have written elsewhere, the nation’s growth miracle occurred under an autocratic leader who worked closely with large conglomerates to develop industries in a targeted manner. Autocracy isn’t per se the problem—China shows that you can have an autocratic government that devolves power to local governments and fosters interregional competition. But Park Chung-hee presided over a unitary system and personally worked with a small list of existing conglomerates concentrated around Seoul. These companies—chaebols—now control the lion’s share of the Korean economy.

Consider SK Group. Among other things, it is an energy company, a pharmaceutical company, and now, with a prospective $56 billion investment, it is seeking to become a leading player in AI. In the US, those industries are represented by individualized companies across the country. An oil company in Houston. A pharmaceutical company in Boston. An AI company in San Francisco. In Korea, they are all wrapped into one company headquartered in Seoul.

There are exceptions. POSCO, the world’s 6th largest steel manufacturer, is located in Pohang, a smaller city in the southeast. But of the 18 Korean companies making the Fortune 500 list in 2023, POSCO is just one of three headquartered outside the Seoul metro area. Besides POSCO, the other two companies focus on natural gas and utilities. Steel, natural gas, and utilities are, of course, very important, but they aren’t the kind of industries defining the future, or that most ambitious young people are excited to work in.

The concentration of large businesses in Seoul does not mean that all of South Korea’s jobs are centered around the capital. Given the predominance of manufactured exports in the South Korean economy, businesses have long set up factories throughout the country. Daegu, for example, became the center of South Korea’s textile industry in the 1960s, while Busan remains a major hub for shipbuilding.

But South Korea’s period of catch-up growth is over. And as the nation pivots away from manufacturing jobs toward a knowledge-based economy, Seoul’s domination of the economy is only growing. In the 1960s, being a textile factory worker in Daegu made sense, but now that such industries have been outsourced to countries like Vietnam or are being automated, more workers are funneling into white collar professions. For a country with as educated a workforce as South Korea’s that isn’t in itself a problem, but given that the best office jobs are concentrated in Seoul, it only fuels the nation’s regional imbalance.

Indeed, the massive gap between the desirability of large company jobs and those at small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)—the subject of my post earlier this year—only makes this worse. South Korea’s expansive use of subsidies seems to have created an economy with a few dynamic export-oriented conglomerates headquartered in Seoul sitting atop a host of low-productivity SMEs. The jobs at chaebols are scarce. Not only do they encourage living in Seoul, but there is strong evidence that young South Koreans are sitting out of the labor market waiting for these positions to open up, further impeding family formation.

The fact that almost all of South Korea’s top universities are located in Seoul doesn’t help reduce this industry concentration. Over 90 percent of students at top 10 universities in South Korea attend classes in the capital, with the remaining students studying at relatively small science and technology universities in Daejeon, Ulsan, and Pohang. (Note that the elite universities in Seoul aren’t as small as their elite counterparts in the US—Yonsei University, Seoul National University, and Korea University, widely regarded as the Korean Ivy League, have a total enrollment of over 100,000.)

Consider, by contrast, the regional pipelines that schools such as Stanford and Berkeley provide to tech companies in Silicon Valley, or Colombia and NYU to finance in New York City. Elite universities have cropped up throughout the US, helping to sustain different regions. Some universities even thrive thanks to the donations of regional tycoons—think of Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh or Vanderbilt in Nashville—thus creating a virtuous cycle of sorts. Given its industry concentration, South Korea has been immunized to this kind of diffusion of top human capital.

Pohang itself illustrates well how the diffusion of industry can help avoid the overconcentration of the best students. Its top university, the Pohang University of Science and Technology, was set up by none other than POSCO, which wanted to cultivate human capital and carry out research close to its operations. But POSCO is the exception within South Korea, and other major businesses have little incentive to create such pipelines outside Seoul.

In an interview I published earlier this year, my Korean friend illustrated well how the shift toward a knowledge-based economy further fuels regional concentration. Her parents were of a generation with few prospects for advanced education, steering them toward a career operating a convenience store in Busan. But she spent her childhood grinding to make it to a university in Seoul, and while she got there, she found it inhospitable to her career ambitions. Did she settle elsewhere in Korea? No—she moved abroad. Only now has she moved back to Busan, where she tutors students who doubtlessly wish to attend a university in Seoul. It’s striking that the younger Koreans I have talked to express a similar notion. For some, the choice is not to live in Seoul or Busan or Daegu—it’s to live in Seoul or leave the country.

Elite students, of course, do not represent most Koreans. But they do play an outsized role in shaping the companies and culture that will define South Korea’s future. And since they are in Seoul, Seoul’s eminence will only be reinforced. That is all the more true in a society that places as high a premium on education as South Korea.

The China Model

Not unlike Seoul, China’s first-tier cities today are experiencing ballooning costs of living as the nation’s urbanization proceeds. But amid this boom, China is seeing a shift yet to be realized in South Korea: young people are spurning the nation’s leading cities in favor of more affordable options. Zhaopin, a Chinese recruitment company, recently found that the nation’s leading second-tier cities have become the preferred destination for white collar workers, surpassing cities like Beijing and Shanghai.

The rise of second-tier Chinese cities highlights a crucial difference in the development models of China and South Korea. While China remains an authoritarian state, it has devolved immense amounts of power to local governments, allowing them to their own tax and regulatory environments to lure in foreign investment and entrepreneurs. More personalized incentives have emerged as well. Changsha is giving “national top talents” a 1.5 m-yuan ($200,000) reward to move there, while Hangzhou is offering startup founders with PhDs up to 15m yuan in funding to relocate.

No city illustrates the impact of decentralization as well as China’s largest southwestern hub, Chongqing. When the princeling (kind of like being a Bush or Clinton in China parlance) Bo Xilai was appointed as secretary of Chongqing in 2007, it was widely viewed as a demotion—the city faced hazardous levels of pollution, entrenched organized crime, and high rates of unemployment. Yet Bo Xilai’s arrival coincided with a reversal in the city’s fortunes.

Bo Xilai’s model has long been described as a left-wing counterpart the free market success of Guangzhou province. Under his direction, Chongqing spent aggressively on public works, such as new housing for recent college graduates, and made socialist propaganda central to the city’s rise. But Bo Xilai’s fundamental understanding of incentives was no different than his “right-wing” counterparts. Among his most consequential moves was lowering the region’s corporate tax from the national average of 25 percent to 15 percent and streamlining the process to launch new businesses. Companies like soon Ford and Hewlett-Packard set up operations in the region, helping the city achieve a GDP growth rate of nearly 15 percent during the Bo Xilai era, well above the national average. (Given the incentives for lying about growth data in China, we should always be careful in taking such figures at face value, but Chongqing’s boom was real, whatever the precise figures.)

Was the Chongqing model sustainable? No—by some accounts, the city was failing to pay local government officials due to its enormous debts. But Chongqing is a perfect example of the impact of China’s political decentralization. A system in which officials bounce around provinces with the authority to create bespoke regulatory and tax environments enables superstars like Bo Xilai to fight for regions that otherwise might be neglected.

Of course, as a communist party secretary, Bo Xilai wasn’t worried about getting re-elected—he wanted to make his case to the Politburo for becoming the paramount leader of China altogether. The incentive in China’s system is not just to earn the favor of a region’s residents, which can plausibly be achieved without Bo Xilai’s wild designs, but to become a transformative force that gains the notice of the central government. In the end, Xi Jinping stood in the way. Bo Xilai was swept up in his rival’s anti-corruption campaign in 2013 and today sits behind bars.

China’s model is hardly perfect, as the widespread graft that accompanied Bo Xilai’s stewardship of Chongqing shows. (Some also prefer electing their leaders.) But as a unitary system, South Korea doesn’t allow much in the way of healthy interregional competition. While Korea did set up industrial parks to the benefit of cities like Ulsan, regional governments do not have the authority to design tax policy or regulations that would draw in entrepreneurs and foreign investment.

It is hard to imagine a counterfactual world in which South Korea developed differently after the Korean War, in no small part because security risks encouraged a more centralized government. But if more of South Korea’s dynamic businesses today were the product of organic entrepreneurship and regional incentives—and not the central government steering existing conglomerates—perhaps other cities could have gained ground on the capital and provided viable alternatives for ambitious young Koreans. A Walton family in Gwangju. A Henry Ford in Pohang. An Elon Musk in Busan. Alas, in South Korea, all roads lead to Seoul.

Seoul’s Density

To summarize, South Korean history abounds with permanent shocks that have undermined cities that should compete with Seoul, fueling the nation’s regional imbalance. I do not have the temerity to assign weights, but I feel confident in saying that:

The division of the Korean peninsula undermined northern cities with strong location fundamentals and increasing returns (Pyongyang), funneling more people into Seoul.

The autocratic development model of Park Chung-hee supercharged Seoul’s increasing returns, creating unusually large incentives for living in around the capital.

But let’s now look at further reasons why Seoul itself is so crowded and expensive. As we discussed at the start, Seoul’s mountainous terrain appears to play a big role in this, but there are, we will see, other factors that have prohibited a more graceful development.

Why Not Remove the Mountains?

In the Chinese proverb “The Foolish Old Man Removes the Mountains,” an old man is so annoyed by a set of mountains obstructing his town that he devotes himself to manually separating them with a hoe. Complicating this otherwise foolproof strategy is that he only has time to make one trip per year for his dig, giving him little time to finish his project. When questioned about pursuing such a futile task, he says that even if he cannot finish in his lifetime, then his progeny will. The gods are so impressed with his perseverance that they remove the mountains for him.

East Asia’s relationship with nature is quite distinctive from that of the West. Compared with the occident, it is more common to find positive depictions of man’s triumph over nature. As the proverb shows, even the Sisyphean task against nature can meet its end with sufficient fortitude. A Chinese version of the Lorax might well end in the gods bestowing a million more trees on the Once-ler for his resourcefulness.

Such sentiments reflect a stark reality: China and Korea have been met with greater antagonism from their natural environments than Western nations. First, there are the resource constraints, with each nation historically lacking sufficient arable land to match its population. Mass famine has struck both the Korean peninsula and mainland China in the past century, owing in part to communist planning, but also to a smaller margin of error in cultivation strategies. Then there is the extensive flooding, which continues to prove a lethal force in both Korea and China to this day. The dramatized depiction of a basement deluge in Parasite was not a total exaggeration—flooding has claimed lives in Seoul as recently as 2022. Flooding in China, of course, has long been identified as a catalyst for state centralization: only a centralized regime could control China’s fickle waterways to make agriculture viable, the thinking goes.

To sum up axiomatically: the west was born with relative abundance, and is attuned to its depletion; the east was born with scarcity, and will fight to take what it can get.

The question, then, is why have South Korean developers been so impeded by the mountainous greenbelt around Seoul? Surely the South Korean government and developer could if not, like the man in the Chinese proverb, remove the mountains, then at least build over them?

It is true that development in South Korea has long been unconstrained by the kinds of regulations common in the West. Until its democratic transition in 1989, the nation showed few qualms about displacing urban residents to make way for new developments. In the lead-up to the Seoul Olympics in 1988—a kind of coming-out party for South Korea—the city razed low-income neighborhoods to put on its best face to the world (this is, quite literally, a face culture). Present-day Guryong Village, among the last shanty towns remaining in the city, traces its origins to this moment.

But a key decision in South Korea’s urban development came much sooner, under South Korea’s second president and first autocratic development hero, Park Chung-hee. It was not, as one might expect, a pro-development choice. Somewhat contrary to the image of South Korea as marked by unconstrained growth, in 1971, Park designated 25 percent of Seoul City a greenbelt where all development is prohibited. That regulation is mostly still in place today.

Park was not without cause. Seoul grew more rapidly than any city in the world from 1950 to 1975, growing at an average annual rate of 7.6 percent. South Korea, recall, was an agricultural society in the mid-20th century. Under Park Chung-hee, it was undergoing one of the fastest urbanizations in human history, with plenty of blight to show for it.

In response to growing concerns about overpopulation in cities, Park implemented his greenbelt policy to help slow the population boom in Seoul and 12 other metros, making over five percent of South Korea’s already limited landmass—specifically around urban areas—off limits for development. This decision was based in part on London’s own greenbelt. London, of course, today faces a large shortage of housing, in no small part owing to this land use restriction.

But there were other motivations for Seoul’s greenbelt policy. Park and his military loyalists, ever attuned to national security, were worried about development in the direction of North Korea, which is just roughly 300 km north of Seoul. Those concerns were also not unfounded: North Korea spent much of the 20th century preparing for a second assault on South Korea, as the tunnels it dug under the DMZ show. A Seoul metro area that stretched even closer to the DMZ would have presented a distinct risk. Security thus became the primary motivation for the greenbelt policy in Seoul by the 1990s, though it is not plausibly so for, say, Busan, which is a southern port.

It is no coincidence then that today, the Seoul Capital Area’s largest cities outside Seoul City sit south of the Han River. Besides Incheon, which has its own status, seven of the nine special cities in Gyeonggi Province are south of the Han, and the two that are north remain Han-adjacent. It certainly looks like security concerns skewed Seoul’s development southward.

Seoul thus had two true constraints on development—the greenbelt, but also a more general reluctance to develop in the direction of North Korea. On a unified peninsula, we would likely see much more extensive development in the direction of Kaesong, as highlighted above.

So far, we have focused on Seoul, but it is worth noting how consequential greenbelts were for all major Korean cities. While cities like Daegu did not have artificial constraints on growth from North Korea, they were still subject to immense land use restrictions. Part of the reason why Korean cities are all so similar, it might be speculated, is that the homogenizing effects of autocratic governance eliminated opportunities for diverse development modes. Besides the fact that cities did not control their land use policies, building capacity was concentrated in the hands of a limited list of state-backed chaebols.

Since 1971, greenbelt restrictions have been relaxed under leaders such as Kim Dae-jung, Roh Moo-hyun, Lee Myung-bak, and Park Geun-hye, with 30 percent of former greenbelt territory now being free for development. More recently, the conservative President Yoon announced plans to eliminate greenbelt protections covering over 20 percent of land in the industrial city of Ulsan, Korea’s seventh largest metro, which has found itself unable to develop new industrial parks due to the restriction.

We should acknowledge the benefits of a greenbelt—in Seoul’s case, it has helped keep high pollution levels down and makes for a nice contrast to the soulless concrete apartment blocks everywhere. Had the greenbelt policy meaningfully dispersed population growth away from Seoul, it might be called a success. But it did not.

In the two decades after the greenbelt policy was implemented, Seoul City’s growth rates were largely unaffected. Looking at the data, we see that Gyeonggi Province also began to grow quickly after the implementation of the greenbelt policy, but Seoul grew about as fast for longer.

One problem was that South Korea’s population was still booming at this time, given that Korean women had a TFR of around six in the 1950s and 60s, a massive generation was coming of age just as the greenbelts had been instituted. And Seoul, of course, remained at the center of an autocratic economic and political machine.

By not allowing Seoul City to expand from its core naturally, the greenbelt policy also impeded integration between the Seoul City area and the surrounding Gyeonggi Province. Officials may have succeeded in preventing Seoul from becoming a sprawling supercity like Tokyo, yet in turn, they made it a highly concentrated one with lots of isolated satellite towns.

Seoul’s world-class subway system helps correct this, but the physical removal of Gyeonggi Province still likely makes these areas much less desirable. Whereas in Tokyo, the line between the suburbs and the city is blurred, in Seoul, it is abundantly clear. If nothing else, this makes suburban living a deterrent to those who want to live “in the middle of things.” It is worth repeating here that the one group not moving out of Seoul City is Koreans in their 20s. Ironically, these residents are likely most sensitive to Seoul’s prohibitively expensive housing, yet they also stand to gain the most from avoiding the suburbs in terms of their career and social life.

A breakdown of Greater Tokyo’s population growth in the 20th century shows a different pattern without barriers to horizontal development. Like the Seoul Capital Area, Greater Tokyo grew immensely in the 20th century, yet unlike Seoul City, the population of Tokyo’s core barely changed at all. From 1960 to 2000, it decreased.

Greater Tokyo was expanding horizontally throughout the latter half of the 20th century, avoiding overcrowding in Tokyo’s core, while Seoul City was still growing vertically past the point it had reached the density of Tokyo’s core. Perhaps Seoul’s terrain never would have allowed for the same kind of seamless horizontal development as Tokyo. Still, one wonders how different the Seoul metro would look today without the greenbelt policy and threat of North Korea.

The Blank Slate

Beyond mountains and land-use policy, remember that the division of the peninsula and war thereafter, remember, had created an influx of millions of Koreans to the south. Under such conditions, there would have been strong incentives for builders to develop high rises to accommodate these crowds.

But there was another important factor that allowed South Korea to build vertically in the post-armistice period: most major cities had been destroyed during the Korean War.

This fact may be lost on many outside Korea, but the Korean War was among the most destructive conflicts in modern history. Some in the US wanted to use tactical nuclear weapons on North Korea, an ambition that was thankfully unrealized. Still, by the end of the war, even cities like Busan and Daejeon had largely been razed.

So when Korea’s growth miracle began, there was little existing infrastructure to stand in the way of new high-rise developments—the many shantytowns that had cropped up in the ruins of cities like Seoul could easily be built over. And as with the greenbelt policy, this had major implications for even cities outside Seoul.

To summarize these anomalous circumstances, we have:

A roughly 30 percent increase in the population due to immigration from 1945 to 1955

Fertility rates on par with sub-Saharan Africa around in the late 1950s/early 60s

One of the fastest urbanizations in world history starting in the 1960s

Little pre-existing infrastructure to be built around

Mountainous terrain

Restrictive national land-use policies in the midst of urbanization

Under such circumstances, high-rise living was overdetermined. Given that housing stock could not keep up with inflows into the city and population growth, the marginal profit from building an extra floor on a high-rise would almost always be positive. Building a low-rise under these circumstances would have amounted to throwing away money. Even on flat terrain like Tokyo, this would have been true.

Many of the European cities that were destroyed during World War II were already part of industrialized economies, with lower fertility rates and higher pre-existing rates of urbanization than South Korea, meaning throngs of new people were not moving into them right as they were being redeveloped. Cities like Warsaw thus took care to recreate the feel of their pre-war environments. For South Korea, rapid population inflows and low levels of pre-existing development ensured this did not take place.

Density as Endogenous Preference

Apartment living in South Korea quickly became more than a matter of exigency post-war. Indeed, not only did the Korean War create a blank slate for high-rise development, but South Korea’s distinctive post-war conditions likely inculcated strong preferences for high-rise living. Unlike in the West, detached housing arrangements implied penury—often literal shantytowns—while monolithic apartments reflected quality and progress. Koreans naturally came to prefer high-rise living to the slum-like conditions that prevailed in many low-rise neighborhoods.

Today, branding and standardization can be integral to an apartment’s appeal. Rarely will you see two complexes sporting the same title in an American city, yet in Korea, because apartments are built by large conglomerates, they often feature the same names—Lotte Castle, Samsung Tower, etc. Korean apartments thus developed along the lines of the automobile, with the option to choose apartment complexes the way one might choose a car’s make and model. And as with automobiles, people choose housing arrangements based not only on utility and amenities, but on signalling value. Living in the Lotte Castle may be a point of pride; living in the unknown low-rise is not.

For Westerners, it is hard to imagine that living in an apartment named after a department store would be enviable—imagine boasting about your unit in the “Target Mansion”—but brand consciousness reflects Korea’s unique development timeline. For Koreans in the 1960s and 70s, name brands provided an anchor to the growing fortunes of a country still in the early stages of development.

Korean apartments also tend to come with lots of amenities, often with families in mind. Unlike most Western apartments, a Lotte Castle, for example, will come with a playground, fitness center, on-site management, and many other perks. Some may even have their own clinics and schools. This contrasts with the US, where apartment developments rarely cater to the interests of families, as Joe Weisenthall has pointed out.

So there are good material reasons for wanting to live in a high-rise, even if you dislike city life. In my own experience, the grounds around brand-name apartments can feel like small neighborhoods. Somewhat ironically, it is the single-family homes and duplexes in the mountainsides of Busan that feel least like neighborhoods—they were built on top of each other on a steep slope with no yards in between (often as many fled the approaching North Korean People’s Army).

For these reasons, Koreans simply like living in apartments more than Westerners. Research suggests the nation is quite anomalous in this regard:

people living in apartments tend to be more satisfied with their residential environments such as amenities, parking lots, and safety from traffic, compared with those living in low-rise residential areas. This result disagrees with that in studies conducted in Western countries that found higher satisfaction levels among residents for single-family detached dwellings than for high-rise multifamily apartments.

It must equally be noted that Korea is a relatively homogenized, high-trust society, and Korean culture tends to be communal (my house in Korean is literally “our house”). There is likely to be less friction from sharing apartments with other Koreans. (I faced no friction living in a unit in Busan, and probably would have thought I was the only one in my building if it weren’t for my neighbor’s occasional hacking cough.) Even so, Japanese people show much more partiality to detached homes, suggesting that Korea’s development conditions played a large role in shaping demand.

There are two interesting manifestations of these preferences. First, the proportion of high-rise apartments is higher in Gyeonggi Province than in Seoul City. This is the exact opposite of what we would expect based on Western metropolises, where building heights shrink as one moves toward the suburbs. It is equally the opposite of Tokyo.

The second is that Korea’s new planned capital, Sejong, is the most apartment-centric city in Korea, with almost 80 percent of residents living in apartments. Even as a fully developed nation, Korea continues to favor high-rise apartments. If anything, these preferences look stronger than ever.

It is tempting to speculate that apartment living is associated with Korea’s low fertility rate. Yet the precise type of housing appears less relevant to fertility than the broader living conditions, as Lyman Stone points out. A studio apartment in the middle of Seoul may well hamper family formation, but three-bedroom suburban apartments may enable it. And Sejong, South Korea’s most apartment-centric city, illustrates this point well. The question is—how much can cities like Sejong move the needle?

Sejong Smart City

South Korea’s leaders have not been blind to the problems stemming from Seoul’s centrality. In 2003, then-President Roh Moo-hyun announced plans to create a new administrative capital, hoping to nudge more Koreans toward the nation’s interior. Four years later, Sejong, a planned smart city 30 km north of Daejeon, broke ground, billing itself as a more affordable alternative to Seoul. Various government ministries have since Sejong, and while construction won’t be fully completed until 2030, the city already has around 330,000 residents.

If the measure of Sejong’s success is its ability to redirect people from Seoul, it would seem on track for failure. While Sejong’s population has swelled since its founding, the Seoul metro population—especially surrounding Gyeonggi province—has continued to grow during the same period, even as other metro areas have begun to shrink. Given how “sticky” population tends to be, it’s no surprise that simply moving government ministries to a city would fail to create a boom town. For Sejong to compete with Seoul, it would need much stronger economic incentives to draw in businesses and entrepreneurs, not unlike those China’s tier-2 cities have used to win over residents from Beijing and Shanghai. Lower cost of living alone isn’t a strong enough selling point.

But Sejong remains a fascinating case study because it is the city most suited to family formation in Korea. The bulk of its housing is family-centered apartments—these are not the kind of studios and officetels that predominate Seoul. And disproportionately, those moving to Sejong are buyers, not renters—they have the means to settle down. With no universities and or nightlife, there is equally limited draw for younger, single Koreans. Indeed, it has been described consistently by the young Koreans I have talked to as boring.

Sejong is potentially more family-friendly in other respects, too. For one, it’s unusually car-dependent by Korean standards. While there is a bus system, there is no subway line, and residents commute via car at high rates—perhaps more amenable to moms and dads who don’t want to lug babies around on the subway. It also has more parks and playgrounds than any other Korean city. In short, Sejong is about as close to an American suburb as any Korean city will ever get.

With these anomalously family-friendly conditions, how fertile is Sejong?

First, a note: Sejong is subject to obvious selection effects. Any Korean person moving there is likely to have stronger preferences for family formation than the typical Korean. Indeed, many move to Sejong precisely because they want to have kids. The effects are all stronger since Sejong’s adult population is entirely made up of recent arrivals.

So as you might expect, Sejong is indeed Korea’s most fertile city or province. The problem is that it still has a rock-bottom fertility rate, with a TFR of just 0.97 in 2023—about the same as Tokyo. Worse still, Sejong’s fertility rate, like the rest of Korea’s, has been declining in recent years.

Sejong shows us that even when urban living is designed with family formation in mind, Koreans choose not to have kids at rates that aren’t much different than East Asian standards. Perhaps apartment living is still an impediment, but it certainly seems like what is happening in Korea goes far beyond issues of housing affordability and density.

Conclusion

Through a series of permanent shocks, the Seoul metro area achieved a disproportionate influence over South Korean life in the latter half of the 20th century. In turn, anomalous post-war conditions, land-use policies, and mountainous terrain helped make Seoul one of the most crowded cities in the developed world.

The high costs of living downstream of these imbalances are not helping South Korea’s present fertility woes, but as Sejong shows, they are not plausibly the largest direct cause of the nation’s low fertility. The fact remains that every region in South Korea—including the one that selects for families—has a fertility rate below that of neighboring Japan and China.

But we should not dismiss the possibility that these regional imbalances indirectly lower fertility. As mentioned at the start, Seoul’s centrality has fueled cultural homogenization throughout South Korea. If Seoul’s low fertility norms are like a social contagion, we might expect them to spill over into surrounding areas given the city’s prominence and proximity. Perhaps Seoul’s low fertility values become Korea’s values, and there are few prospects for minor cities like Sejong to challenge to the prevailing norms in Seoul.

We should consider, then, the values that prevail in Seoul in depth. That is for another date.

good post, slight nitpick. i think its a bit misleading to say Gyeongju is not even one of the 40th most populous city in the korean peninsula given that wikipedia's list of the most populated cities in south korea, (where i assume you got this info from) includes many cities that are part of seoul's metro area. wouldnt you want to count those all as one city?

(by my count, around 20 cities, more populous than Gyeongju, are in the Gyeonggi province)

Korean in USA have similar fertility ratehttps://x.com/lymanstoneky/status/1642907812639408130?t=fQUh3G67s77xWMNsosS2_A&s=19