Did an Alphabet Make Korea More Verbal?

And long-term implications of difficult writing systems

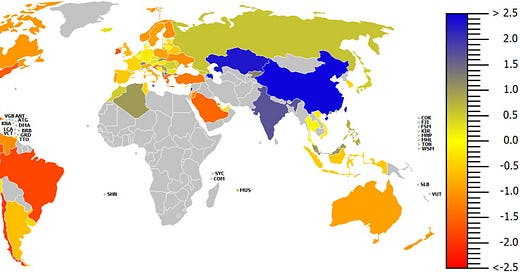

A map has been making the rounds on X showing math and reading tilt in PISA scores by country. It comes from a study published over a year ago, which analyzes PISA data from 2000-2018.

Users describe the map as reflecting a quantitative tilt in East Asia. While this is true overall, the region’s major countries still vary considerably. China exhibits the most quantitative tilt, although Macao and Hong Kong notably skew less quantitative than mainland China. Japan shows less (but still significant) quantitative tilt than China. Curiously, South Korea actually shows a verbal tilt. If we extend to Southeast Asia, we notice Vietnam presents balanced PISA scores, if not a slight verbal tilt as well. If the narrative here is supposed to be “those Asians and their math brains,” we might expect less variation, at least among South Korea, Japan and China.

Why might Korea be the outlier here? And why might Macao and Hong Kong deviate from mainland China? One explanation is cultural—South Korea, Macao, and Hong Kong all share in being heavily influenced by Western culture, whether through outright colonization in the case of Macao and Hong Kong, or the spread of Christianity in the case of South Korea. Perhaps engagement with more verbal cultures led to more investment in literacy among natives.

I think this could be right, but I would like to also posit a linguistic explanation. Notably, while Chinese, Japanese, and Korean share some history, they vary considerably in their writing systems today.1 Chinese is written purely with logograms, and Japanese is written with a hybrid of Chinese-derived logograms (kanji) and two syllabaries (hiragana for native vocabulary and katakana for English loan words). By contrast, Korean uses a featural alphabet (hangul). Extending to Southeast Asia, Vietnamese uses a modified Latin alphabet (chữ Quốc ngữ). Perhaps these different writing systems are producing different tilts.

Looking at the PISA data again, the pattern in East Asia lends some credence to this idea: the two major East Asian countries with logographic writing show a quantitative tilt, while the one with an alphabet skews verbal. Vietnam also shows no quantitative tilt despite abutting China and having a long history of Chinese influence. What about Macao and Hong Kong, which show less tilt than China? Recall that English is used as a language of instruction alongside Chinese in these regions, so some students are actually taking the PISA exam in English. Between Hong Kong and Macao, the former, where English is more common in schools, exhibits less quantitative tilt than the latter.2

Why might logographic scripts create a quantitative tilt compared to alphabets? The simple answer is that they present higher upfront costs for learning to read. Whereas alphabets have 26 or so characters, logographic writing systems have tens of thousands. Also recall that alphabets have phonetic content. A general feature of this system is that I can read and identify words I have never seen printed before if I am already fluent in the language, as students learning to read typically are. This might not seem important now that I have been reading for almost two decades, but when learning to read it is very handy.

The lack of phonetic content in logographic writing precludes the use of phonics, the most effective method of learning to read for alphabet-based languages.3 How do students of logographic languages learn to read? Chinese students spend hours a day just copying and memorizing characters in school to achieve literacy.4 All else equal, the higher initial hurdle and greater risk of attrition likely create more stragglers and incentivize greater investment in math and science, even if many children take to the challenge. Thus, even as absolute reading scores are high in China and Japan, perhaps they could be even higher if the nations eschewed Chinese characters.

These are just theoretical considerations. But the history of Korea and Vietnam’s writing systems offers some empirical evidence that alphabets promote greater literacy. In fact, neither of these nations are unfamiliar with logograms. Before embracing the alphabet, each nation used Chinese characters for centuries.

The ABCs of Writing Reform

It is not clear when Chinese-derived hanja first entered Korea, but evidence dates back to the 3rd century BC. For over a millennium thereafter, hanja served as the primary means of written communication in Korea.

In the 15th century, the ruler Sejong the Great took stock of what has already been observed: Chinese characters require lots of time-consuming memorization. In an effort to bolster literacy, he sponsored the development of hangul to replace the Chinese-derived hanja.

Hangul is arguably even more clever than your typical alphabet. It is often considered “featural” because each letter represents the shape a mouth makes during pronunciation of the corresponding phoneme. Letters are also combined into blocks to create full syllables. If you have ever thought Korean hangul looked very different than a typical alphabet-based script, this is why. Yet fundamentally, Korean uses letters, just like English.

The “Great” in Sejong’s name testifies to the success of hangul. South Korea’s literacy rate increased upon the adoption of hangul, expanding opportunities for political and religious organization over the next several centuries. Greater literacy and the relative ease of translation into hangul likely aided in the spread of Christian texts. This may explain in part why Christianity today is far more common in South Korea (~25% of the population) than either Japan (~1.5%) or China (~1%).5

South Korea’s literacy rate was by no means high in the centuries following Sejong’s reign. In 1945, it sat at just 22%, owing at least in part to the nation’s subjugation by the Japanese. But when South Korea began to develop following World War II, literacy rates rapidly rose. By 1970, about 88% of adults were literate.

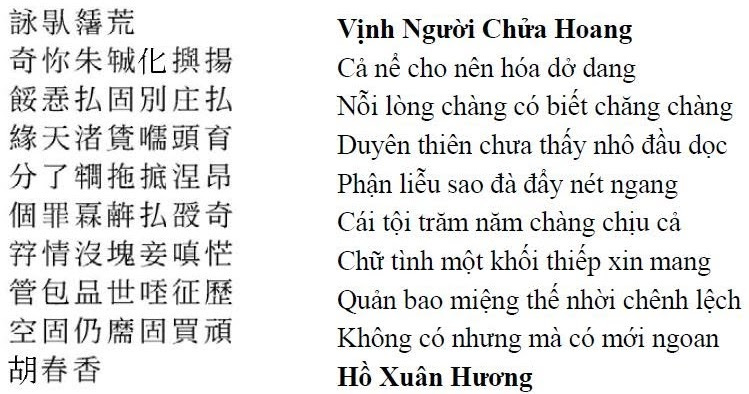

Though it took longer to implement its alphabet, Vietnam underwent a similar transition after using logograms for roughly two millennia. Before the 20th century, Vietnamese used Chinese-derived Chữ Nôm, but with French occupation, schools began enforcing the use of Chữ Quốc ngữ, a Latin alphabet based on the original designs of the 16th-century Jesuit missionary Francisco de Pina.

Chữ Quốc ngữ may have begun as a colonial imposition, but it quickly became a tool for mass education. As in South Korea, the relative ease of learning an alphabet made for an especially swift literacy campaign. In 1945, only 5% of Vietnamese were literate. By the end of the First Indochina War in 1954, 93.4% of people between the ages of 12 and 50 in North Vietnam could read and write. After the Vietnam War, 94% of South Vietnamese could. Not bad, considering the circumstances.

Mass literacy campaigns also succeeded in China, but the existing data suggest they may have taken longer. Between 1949 and 1959, the literacy rate for those between the ages of 12 and 50 rose from 20% to 57%.6 Admirable, but much less impressive than North Vietnam. China’s size of course makes coordination more difficult, but getting rural farmers to memorize thousands of logograms is an inherently taller task than getting them to memorize the 26 or so symbols for phonemes they already know. Here is an account of the relative ease of Vietnam’s literacy campaign:

Once we used a ladder to paint 23 huge letters on the wall, everyone who walked by could see them clearly. On market days, we took turns guarding the road and testing the people. Whoever could say the letters could stay on the road, but those who couldn’t had to wade through the canal.

Had those characters been just 23 out of several thousand logograms, there probably would have been many more wet peasants on those market days.

Implications

Countries may choose difficult writing systems, but it worth considering the consequences.

First, logographic writing may make the upfront costs of learning to read well higher, pushing more kids toward math and science and likely depressing reading scores, even if absolute scores are high. Depending on one’s priorities, this may not be all bad. If you are leery of a nation of lawyers and poets, perhaps a tax on reading is the way. Has too much magical realism enfeebled Latin America’s economic discernment? If one wishes to pursue a fuller Sapir-Whorf line of reasoning, perhaps logographic writing systems hone spatial abilities directly.7 I leave this to you.

Second, even if logographic writing systems do not drive lower reading scores among natives, a logographic writing system makes immigration more difficult, especially for high-skill workers. Learning a language as an adult presents a greater opportunity cost already, and this only increases with logographic writing system. If Mandarin truly takes 1,100 more hours to learn than Vietnamese for an English speaker, then Vietnamese looks like a bargain.

Few Americans are itching to immigrate east, but within Asia, many Southeast Asians would like to immigrate to Japan or South Korea. The difference between hangul and kanji may inform these migrants’ preferred destination at a time when both Japan and South Korea face sub-replacement fertility rates. Currently, South Korea’s fertility rate is the lowest in the world, and it has been more restrictive of immigration than Japan in recent years. Yet its relatively simple writing system remains a comparative advantage in attracting talent if and when the country expands immigration.

Finally, logographic writing may influence a nation’s ability to participate in idea exchange. In the case of China, this could undermine its increasingly global ambitions. Xi Jingping may build roads in cities like Nairobi, but it will remain easier for Africans to learn to read Indo-European languages and engage with Western ideas in media, especially as many already speak an Indo-European language as their native tongue. While proficiency may remain low in English at a continental level, existing educational infrastructure and lexical similarity with other Germanic and Romance languages in the region will make English acquisition quicker for Africans, writing systems aside. The same is obviously true for Latin America, where China continues to expand relations.

China is trying nonetheless. The Confucius Institute seeks to expand the nation’s soft power in Africa through language education, but for the reasons above, I would not hold my breath over such efforts. In 2019, an optimistic account of China’s efforts mentions mere hundreds of schoolchildren proficient in Mandarin, and Mandarin language education remains low priority for most Africans. In countries such as Kenya and Uganda, Mandarin is now offered as a foreign language in schools, yet it must compete with a melange of alphabet-based languages, such as German, French, Arabic, and of course English.

Even if China is unlikely to succeed in promoting Mandarin language education, Japan may offer a counterpoint to the necessity of grooming foreign language experts. Despite the paucity of Japanese speakers outside Japan, the nation continues to export much of its popular culture in translation. Living in Honduras, I have been struck by the popularity of anime in the country. Besides the many Dragon Ball Z shirts, a student at my school in Honduras actually has a lunch bag decorated with random hiragana.

But Goku in translation does not enable the export of more fundamental patterns in thought, which increasingly spread via the decentralized channels of social media. If one only knows Dragon Ball Z and Resident Evil, one knows very little about Japanese culture indeed, other than perhaps its affinity for epic displays of violence.8 Much of the exchange of core ideas and values now happens in the digital public commons, where translation is cumbersome and often inadequate. The best hope is that love of anime and video games will inspire Japanese language education, but such an investment is too much for even many of the most ardent weebs.

Conversely, China may reap short-term benefits to regime stability from linguistic autarky. Christianity’s spread in South Korea suggests that easier writing systems may enable the import of values just as much as the export. Similarly, the Japanese syllabary katakana has enabled the swift adoption of loan words for Western inventions and ideas, such as the department store or television. Linguistic insularity may therefore reduce concerns about Western rabble-rousers inserting their ideas on Chinese platforms. Consider how many English-language tweets come from outside the Anglosphere (and by extension how few Americans and Brits realize they are often engaging with foreign ideas). For a nation suspicious of all but Xi Jingping Thought, logograms may be a buffer against competing values in the internet age.

Still, if China wishes for Mandarin to contend with English globally, it need not look far: the Latin script pinyin already exists for typing. In a twist of irony, the reason pinyin has not already been adopted as China’s official writing system may owe to the sagacity of the US’s last Cold War foe. According to Zhou Enlai, who created the script at the behest of Mao 1949, it was Josef Stalin who told Mao not to adopt the script. Stalin, in his infinite fondness for cultural diversity, supposedly viewed Chinese characters as a point of national pride for the budding nation. A nifty idea, but perhaps it is time for China and Japan to heed Sejong’s wisdom.

As a commenter points out, the relationship here is not so simple. Korean and Japanese are from a different (and possibly common) family than Chinese, but by some estimates over half their vocabulary is derived from Chinese. If we are focusing on differences, though, Chinese grammar is generally thought to be simpler than that of Japanese or Korean.

I would also add that Taiwan, which is less immune to Western influence than China, marches in lockstep with China in terms of tilt.

Notably, educational efforts to treat English words as logograms have produced poor results.

Some have described Confucian influence as emphasizing memorization in Chinese education more generally, but its seems this may just be a product of the very nature of the Chinese characters. That is, it seems more likely that Confucian emphasis on memorization was a response to the demands of reading Chinese, rather than that Confucians thought memorization was especially useful relative to Westerners prima facie.

It would be interesting to see how South Korean Christians compare to non-Christian South Koreans in reading scores.

All of this data should be taken with a grain of salt, but if one assumes both nations are exaggerating, it is curious that Maoist China would exaggerate less.

This is not a complete joke. There is ample evidence that literacy affects spatial abilities, and dyslexics have long been thought to have enhanced spatial abilities. Could logographic writing guard against certain spatial deficits associated with literacy?

One might be more optimistic about reality TV. The Japanese TV series Terrace House provides a more intimate portrait of Japanese life, although it is a mere sleeper hit internationally.

The fact of India's strong math skew likely needs explaining in light of your theory. Most (all?) of the subcontinent's writing systems are alphabetic. One possible explanation might be the diversity of languages, and students taking the test in languages that they speak less regularly. Or it could just be that the philosophy of education is just very different there from East Asia. Any thoughts on that? Regardless of the explanation, it's a clever theory and I'm always down for fanboying over Hangul.

India's writing systems are mostly abugidas, not alphabets

No children are taking the exam in a language they are not used to...that would be very silly.