In 1966, Kim Jong-il, later to become North Korea’s Supreme Leader, joined his nation’s Propaganda and Agitation Department, where he was quickly made director of the Motion Picture and Arts Division. It was a seamless fit: Kim was by all accounts a genuine cinephile, having amassed a personal library of 15,000 films. Even the younger Kim’s detractors would admit his artistic flair, though little else about his capabilities.

Given these developed tastes, Kim apparently had a hard time overlooking the fact that North Korean cinema was pretty crappy. In a bid to breathe new life into the medium, Kim did the obvious thing, and orchestrated the kidnapping of the South Korean actress Choi Eun-hee from a Hong Kong hotel in 1978. Upon arrival in Nampo harbor, Choi was locked in a luxury villa, where she was re-educated and forced to serve as a critic of the regime’s film and opera.

While nabbing a starlet was a minor victory for the regime, Kim’s true design was much greater: luring Choi’s husband, the celebrated South Korean director Shin Sang-ok, north of the DMZ, where he would be forced to produce movies with Choi. When the South Korean director didn’t budge, Kim again did the natural thing, and orchestrated the kidnapping of Shin Sang-ok from Hong Kong six months later.

Kim’s plan worked better than expected—Choi and Shin ended up making several movies for the regime, one of which would win a Czechoslovakian film award. But the success proved short-lived: Choi and Shin escaped via an embassy in 1986 before the collapse of global communism left North Korea’s film industry to whither.

Forty years on, you are much more likely to have seen a South Korean movie than a North Korean one. South Korea, of course, used a very different approach to developing its culture industries—rather than kidnapping proven directors, it relaxed the censorship of artists following its democratic transition in 1989. By the 2000s, with some hands-off subsidies for promising auteurs, South Korean media had become an international sensation.

Today, one could make the case today that South Korea is the locus of cultural power within Asia. Hijab-sporting youths in Indonesia line up to see BTS, Blackpink tops the charts in Singapore, and Japanese women swoon over the idealized depiction of Korean men in Winter Sonata. On the YouTube channels I use to learn Korean, Nepalese enthusiasts of Korean culture are omnipresent.

All of this is an inversion of the long-standing order in Asia. Historically, China, literally the “middle nation,” was the center of the Asian world. Nations like Japan and Korea paid heed not only to China’s hard power but also to its cultural offerings. Today, over half of Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese vocabulary derives from Chinese. To make a crude analogy: China was to its peripheries what Rome was to the West.

The present inversion is not without controversy. For example, Chinese and Korean netizens beef over the semantics of pickled cabbage, a controversy that would appear pulled from a lost chapter of Gulliver’s Travels. Recently, when a Korean netizen claimed in a forum that Shanghai didn’t have many luxury vehicles, the city’s trust-fund kids turned a touristy area into a parade of Bentleys and McLarens.

Whether South Korea is truly the locus of cultural power within Asia, it seems safe to say that China, a nation of 1.4 billion, punches well below its weight in its culture industries. In the US, despite all the hubbub about a “second Cold War,” more college students are studying Japanese, the official language of robotic nursing homes, than Mandarin.

And while China is certainly not North Korea, one apparent reason for China’s struggles is that not unlike the North Korean regime, the CCP does not give its citizens nearly as much room to operate creatively as their South Korean and Japanese counterparts. There is, of course, still much Chinese pop culture to be lauded—science fiction stands out, perhaps because the genre’s otherworldly focus grants writers more creative liberty.

But in cinema, for example, scripts have to be submitted for review. Even films aimed at international audiences are now subject to state review, dampening China’s efforts in the international film festivals that South Korea has come to dominate. It seems beyond coincidence that much of the most celebrated Chinese cinema in recent history was made in a British colony of 7 million people.

Under Xi Jinping, censorship has only increased. The idol culture that has driven the success of K-pop, for example, is verboten. Recently, the CCP cracked down on a booming micro-drama industry, in part due to an insufficiently Marxist trope about people getting rich through a sudden windfall. Sometimes Chinese creators cannot even own their exports—the state censors the popular “Boys’ love” genre of fiction domestically even as it has found a large audience in neighboring Thailand.

But various congressmen, national security experts, and other septuagenarians claim that China now has a new weapon in its soft power arsenal: TikTok, the Chinese-owned social media platform that has captivated Gen Z. Through TikTok, critics claim, the Chinese state can pull algorithmic levers to beam pro-CCP propaganda directly into vulnerable, developing brains—no sissy literature required. A generation raised on TikTok will then, I guess, refuse to fight for Taiwan or something.

It is a nifty idea, but is it actually so simple?

While we are still awaiting peer-reviewed studies on the effects of CCP propaganda on malleable prefrontal cortexes, we now have a peer-reviewed Rutgers study on TikTok usage and attitudes toward China. TikTok users, it appears, rate China’s human rights record more highly than non-users. Worryingly for the study’s authors, they’re also more likely to want to visit the country that makes up 20 percent of the world’s population. According to one liberated outlet, the study, which arrived just in time for TikTok’s going dark, shows that TikTok “brainwashed America’s youth.”

Grim stuff. But is that actually what the study shows?

No, it shows that people who report they use an app that most Americans think is a tool for Chinese influence have more favorable attitudes toward China. That is very far from finding that TikTok’s content made people hold more favorable attitudes toward China. Correlation, causation, etc. And yet, the study’s author concludes, “Scaled indoctrination isn’t hypothetical. It’s real.”

Another reputable outlet, the Financial Times, recently published an article suggesting that TikTok may be pushing Taiwan’s youth toward the CCP. To be fair to the FT, which I quite like, no hasty conclusions are drawn in the article, but since this is such a complex thing to try to tease out causality on, we might expect some really impressive data to back up any speculations.

The FT highlights two bits of data: 1) younger Taiwanese have become less likely to identify as Taiwanese over the past six months 2) younger Taiwanese have become more likely to identify as Chinese over the past six months.

Wait, six months? TikTok has been out for six years, but we are only looking at the past six months? Did all of Taiwan’s youth recently start using TikTok? Is CCP propaganda of the extended-release variety?

And notice the fancy graph produced—on one grayed-out trend line, you’ll see that the increase in identification as “Chinese” was even greater with senior citizens over the period in question! Is TikTok making 70-year-old Taiwanese people more likely to identify as Chinese than 20-year-olds?

It’s true that the 20-24 age bracket saw the steepest decline in identification as “Taiwanese.” But there may just be a growing dissatisfaction with Taiwan’s government among young people, which judging by the giant brawl on the parliamentary floor last month, does admittedly look like a bit of a shitshow. The rush to blame TikTok is strange considering that only around 30 percent of Taiwanese between 18 and 29 even use the app.

So there is still no strong evidence that TikTok’s content is shaping attitudes toward China in a meaningful way. But the meta-lesson from the Rutgers study and FT report is that, for a journalist or academic, it would be a great story if China could tinker with an algorithm and make people PLA patriots. That’s, like, MKultra-level stuff.

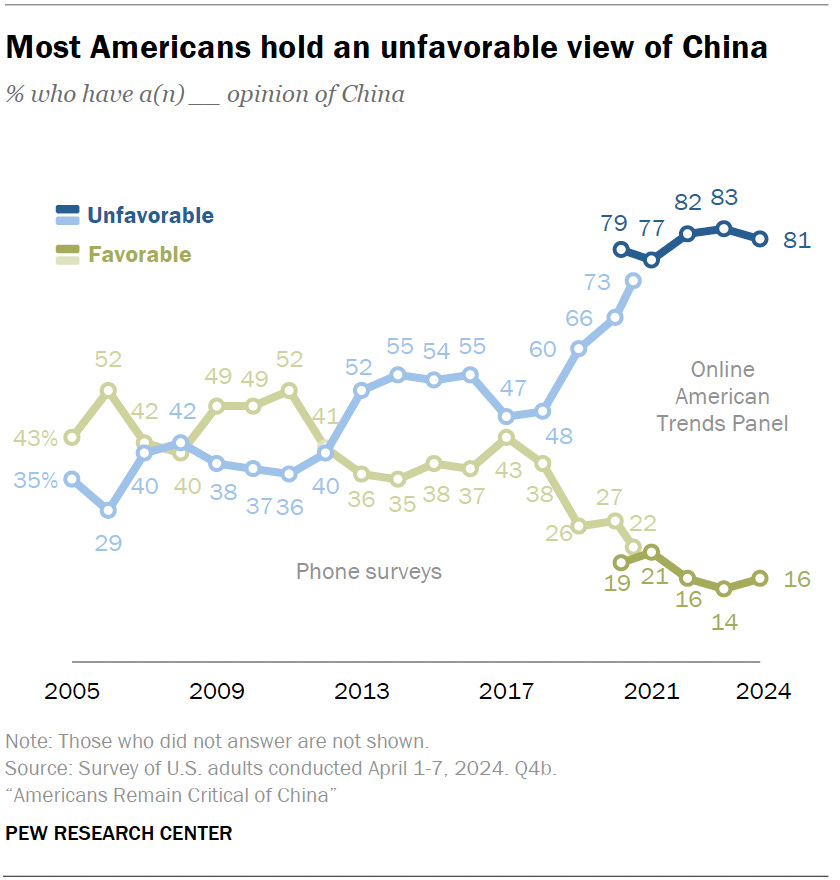

Not only does China likely lack these capabilities, but there is a lot of evidence that China is just not very good at winning friends and influencing people. Most people in the developed world have much worse attitudes toward China than they did when TikTok was founded, and most Americans now believe trade with the world’s second-largest economy weakens national security. If a propaganda campaign is succeeding, it is not one conducted by the Chinese government.

Some of this negative sentiment likely stems from COVID and the disastrous “wolf warrior” diplomacy. But you should ask yourself how sophisticated China’s propaganda efforts are if a foreign ministry spokesman thought posting a computer graphic of an Australian soldier cutting an Afghani child’s throat was a good PR move.

These chilled attitudes were very palpable when I taught in South Korea, and not a single student mentioned wanting to visit China during a travel discussion. Probably half the kids mentioned Japan, which once colonized Korea and tried to stop Koreans from using their own language, but no one wanted to visit China, which, in case you have never looked at a map, is right next to Korea. Nor could I find a single student studying Mandarin, though some students were studying Japanese and Spanish. The one facet of Chinese culture that seemed to resonate with students was malatang, a spicy hot pot dish from Sichuan. Oh, and TikTok.

An obvious reason for the Sino-skepticism among my students is that China backs North Korea, which very vocally threatens the annihilation of their nation. But wait—do American teenagers not also know that China backs North Korea and that this nation regularly threatens the annihilation of their own nation? If the answer is “no,” do you think TikTok is the reason they are unaware of this?

No, because to those outside China, the CCP’s propaganda efforts do not work in a vacuum. China can try to enhance its global image by calibrating algorithms to its liking, but people eventually learn the CCP is using underhanded tactics to enhance its image, or that it props up transparently malicious states, or that it is just generally authoritarian in a way that is off-putting to most people who enjoy civil liberties. And so whatever benefits of suppressing “Tiananmen Square” or “Winnie the Pooh’ are outweighed by the very bad vibes that China gives off by being seen as authoritarian and manipulative.

Actually, let’s imagine for a moment that China really is gaining influence with TikTok users as some judicious social scientists believe. Is this really the boon for China’s soft power so many assume? If you zoom out, it appears not, because China is clearly losing influence with people of voting age, who now view the nation as preying on 15-year-olds. Remember, over half of American adults now think TikTok is a “tool for Chinese influence.” On net, you could reasonably argue that by (apparently) suppressing certain topics, TikTok has been worse for China’s image in the US than if it had made a Tiananmen Square massacre documentary mandatory viewing for all new users.

A simple way of thinking about this is that by the time you’ve read a headline that claims China is manipulating 15-year-olds, its manipulation campaign (real or imagined) has failed. The only way such a campaign works, in the long run, is if you think that TikTok users are so brainwashed that their attitudes toward China are set for life. But remember, even social media platforms have a half-life. And in the Rutgers study, TikTok users didn’t even have very favorable attitudes toward China—they gave it less than a five on average for human rights.

One problem with China’s PR efforts is that they are calibrated for a closed society. The underlying principle is that if people see only good things about China—China builds cool stuff, China definitely does not kill people during protests, etc.—they will like China more. This might work if you can censor all opposition, but it fails when people can investigate and promote contrary information. As the Streisand effect shows, the harder you try to suppress a topic on an open internet, the more attention you draw. Many Western internet users today appear to learn about the Tiananmen Square massacre precisely because of China’s efforts to censor it.

And it is not even clear how good China is at containing information at home. Chinese people have long maintained their own term for the Streisand effect: "wishing to cover, more conspicuous" (欲蓋彌彰, Yù gài mí zhāng). Many young Chinese people today use VPNs to circumvent the Great Firewall and are not oblivious to the touted examples of authoritarian overreach, whether they care about them. Consider that the point of China’s censorship abroad and at home is not so much controlling what people know as setting the terms of what people can talk about domestically without facing reprisal.

A final consideration is that as a private company in a competitive social media space, TikTok faces a tradeoff between propaganda efforts and maintaining its edge. If TikTok actively seeks to promote too much content per the CCP’s wishes—and doesn’t simply suppress a few rarely sought topics—we might expect it to lose market share in the long run, as it will be at a disadvantage compared with competitors who optimize for content users want to see instead of what the government wishes to be promoted. In this way, there is a check on the extent to which the CCP can abuse TikTok—exert too much control, and the users may leave for a rival platform.

So what does the effective development of soft power look like? Let’s consider South Korea’s success again. One could reasonably argue that media like Parasite and Squid Game have enhanced perceptions of South Korea. Unlike TikTok, which is essentially a form of infrastructure, people who consume this media are forced to engage with storylines about Korean people. (This is actually a pretty intimate thing when you think about it.)

The great irony, though, is that much of this media does not portray South Korean society in a flattering light. The not-so-subtle message in Parasite and Squid Game is that South Korea is a ruthlessly competitive place with entrenched inequality. If we throw in the award-winning film Burning (in which a hapless young writer murders his crush’s wealthy suitor) and TV drama SKY Castle (in which Korean people murder each other to get into one of Korea’s top universities), a common theme in Korean media would appear to be literal class warfare! Inter-class homicide is very far removed from Xi Jinping’s vision of “common prosperity,” and yet such content increases South Korea’s global status.

Or consider the Taiwanese brawl I alluded to. Taiwanese parliamentary brawling is actually kind of a tradition, in case you didn’t know. And you could interpret this two ways—a CCP henchman might tout this as proof that Taiwan’s democracy is fatally flawed—look at the dysfunction! But watching videos of the Taiwanese chamber turn into a cage match, I actually found myself liking Taiwan more—I was like, “Oh, Taiwanese politicians are real humans, who are flawed and fight and stuff.”

Actually, someone in the comments of one video summed it up well:

“Taiwanese people are so fucking awesome.”

What? An image of Taiwanese strife and dysfunction makes people like Taiwan more? Well, yeah, most people like signs of humanity, not sterile, machinelike politicking. Suffice it to say, you will never find a story about a brawl during a Politburo meeting in China, though, honestly, if I heard Xi Jinping threw a punch, instead of how many times he’s read the Water Margin, I might feel a bit more partial to the whole social credit score thing.

I think this is a bigger point: countries that cultivate lots of cultural capital do so by owning their weirdness, flaws, etc. Countries that constantly signal that all is perfect in the best of all possible worlds end up with this affect:

(Incidentally, it was long rumored this song was based on China’s response to the Tiananmen Square massacre.)

So color me not worried about TikTok as a tool for mass CCP brainwashing. Perhaps the more compelling argument against TikTok is that it might be used to surveil American citizens. National security experts warn that in light of China’s 2017 National Security Law, which allows the government to force companies to disclose sensitive user data, the CCP could harvest troves of information about American citizens.

I will reveal myself as an idiot here because sometimes it is useful. What data could the CCP hypothetically be harvesting to its advantage? Fast fashion trends? Location data? Is the CCP going to send a drone strike on Tibetan immigrants in California? (Note here surveilling Wumao patriots: A premise for Wolf Warrior 3.) Some suggest it will be used for gathering kompromat on future government officials, but what exactly is the kompromat? Liking pretty girls dancing? Do you know how many mistresses the average CCP politburo member has?

ChatGPT can certainly gin up some interesting use cases for all this data, but the bigger picture is that this kind of data is more ubiquitous than ever. If you are worried about who might get their hands on TikTok’s data, Amnesty International, a fine, Soros-backed NGO advancing human rights around the world, makes the obvious point: why stop at TikTok? All of Big Tech is based on a “surveillance-based business model.” Couldn’t Mark Zuckerberg hypothetically use location data from Instagram to order a drone strike on some guy who made fun of his new gold chain getup?

More seriously, isn’t all this privately held data vulnerable to cyberattacks by China? (The national security experts, bludgeoning me over the head with their Georgetown master’s degrees, are telling me, verily, it is.) Actually, there is evidence that China has been using platforms like Meta and X to gather data for years now. Surely they will eventually crack these platforms’ private data, if they haven’t already considering Meta’s many leaks. So why not just nationalize Big Tech and keep all this data in a big government-protected vault in Nevada or something? Don’t you take national security seriously?

This is a slippery slope argument, but realize that the national security arguments about TikTok are also slippery arguments. “If we allow a Chinese company to collect American user data, then China could harvest this data to its advantage.” See the slope in the first clause, and the slip in the second. The real question is which slopes you are willing to stand on. Some national security experts never answer this question, instead pointing out the most fashionable slopes to worry about.

And while worrying about what China might do with user data is very fashionable, few seem to care that allies like the EU are already trying to force Big Tech to unlock encrypted messages and user data. (Don’t worry—De Bolle insists it’s to protect democracy.) The reality is that few countries are actually committed to data privacy if it doesn’t suit their immediate interests.

Perhaps we should inure ourselves to the idea that if national security hinges on protecting the data of 14-year-olds from adversaries, we are already screwed. That doesn’t necessarily mean we should overlook proven cases of the CCP harvesting data to its advantage, but to date, no evidence of such cases exists.1 And given the controversy surrounding TikTok, if I were a CCP Mandarin, I might be inclined to pursue other, less monitored channels as a source of kompromat anyway.

Even if TikTok isn’t a big deal, it might seem that forcing a sale of the platform is a harmless intervention. After all, China bans Western social media apps domestically. But the idea that the government should intervene against a private platform strikes me as a bad precedent when plenty of bureaucrats and senators would like to get their hands on adjacent companies. China hawkishness is the current national security fad, but there will be new ones to come—just hope you’re on the right side of them.

There was a case of employees surveilling journalists to try to track leaks, and those employees were fired.

Ran this by my friend who has been very invested in this since the congressional hearings and who only lurks on substack, so I am posting (with permission) on his behalf:

this is a fundamental misunderstanding of the threat of tiktok

in the US, because we're a free and open society, you will be able to find hundreds (thousands?) of people who believe anything

just among US citizens there are several hundred thousand unironic communists, ten thousand+ chinese nationalists, many thousands of flat earthers, take your pick

so if you, the director of TikTok, want to push a specific narrative on behalf of the CCP, you don't have like, a directorate of hot girls with security clearences make english language dances about how US support for Israel is morally bankrupt, or something

you just find the existing americans making content that aligns with your goal of the moment and add +81000% to their content in the algorithm

you basically take anything that isn't what you want to promote, remove it, then take anything you can find that aligns with your interests (but was organically produced by americans for americans) and signal boost it to the moon

further points for the comment, wherever they make sense: TikTok is not likely to dump its influence on causes that won't work, because they're actually smart -- so they'll push much more heavily on causes that are much more subtle than CCP good/bad, but that still align with Chinese interests, and one of the big ones there is just spreading "USA bad" content

look how many young Americans think the USA is bad for the world

is that number higher because of TikTok, and can the CCP use TikTok as one tool in the arsenal to get that number up as high as possible?

me: sounds like you're modelling the ccp as having some people who actually have international tact

him: not so much international tact as the ability to run A/B tests and see what's working, which TikTok does better than anyone else in the world just in the normal course of producing the most addicting algorithm

they presumably tried to push on like, "CHINA UNDER CCP GLORIOUS LEADERSHIP GREATEST COUNTRY EVER" content and got ~zero traction

then tried pushing on like, "USA BAD because [insert cold war event with slanted storytelling]" and got much better traction

and obviously they're smart enough to see that those sorts of narratives having traction in the american public is of strategic value

there's also the piece where more overt influence is a loaded gun that they can fire (only once) at a time of their choosing - even relatively unsophisticated propaganda a la north korea (but from a trusted source) can be very useful in, say, the 24 hours after a chinese invasion of taiwan when everyone is dazed and confused and shouting

where "very useful" is just code for muddying the waters and spreading additional confusion / dissent