Why Thailand Isn't Poor

The merchant kingdom

Pretty much every majority-Buddhist nation is poor. The one notable exception is Thailand, an upper-middle-income country. The question, per a conversation between Tyler Cowen and the preeminent Buddhism scholar Donald Lopez, is why Thailand is not so poor.

If you are an academic and someone asks you why Thailand is the wealthiest Buddhist nation, the right response is to deploy the stock phrase, “because it wasn’t colonized.” Such an answer hits all the marks of good academic theorizing—anti-colonial, acultural, and West-weary.

It is also not a satisfying answer. Some places that were colonized are wealthy today, and “not being colonized” tells us nothing about why Siam escaped conquest in the first place. We should just as well consider the opposite hypothesis: Thailand avoided colonization because it was already more modern than its neighbors. Donald Lopez hints at this when he mentions that Siam, unlike its neighbors, engaged in trade.

I am not arguing that this is the only reason. Siam had some geographic fortune in the context of Southeast Asian colonial competition. Because it was wedged between Burma and Indochina, it formed a natural buffer state for competing British and French ambitions. Siam’s neutrality was an easy compromise for Britain and France as their regional land grabs came to an end in the late nineteenth century.

Still, it is unclear that Siam would have gone uncolonized had it looked more like Vietnam, with its scholarly Confucian elite, or Burma, with its insular military aristocracy. Escaping colonization required legwork on Siam’s elite—openness to legal and constitutional reform, and the ability to raise revenues to pursue such reform. The deeper question, then, is why Siam managed this where its neighbors—Burma, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam—did not.1

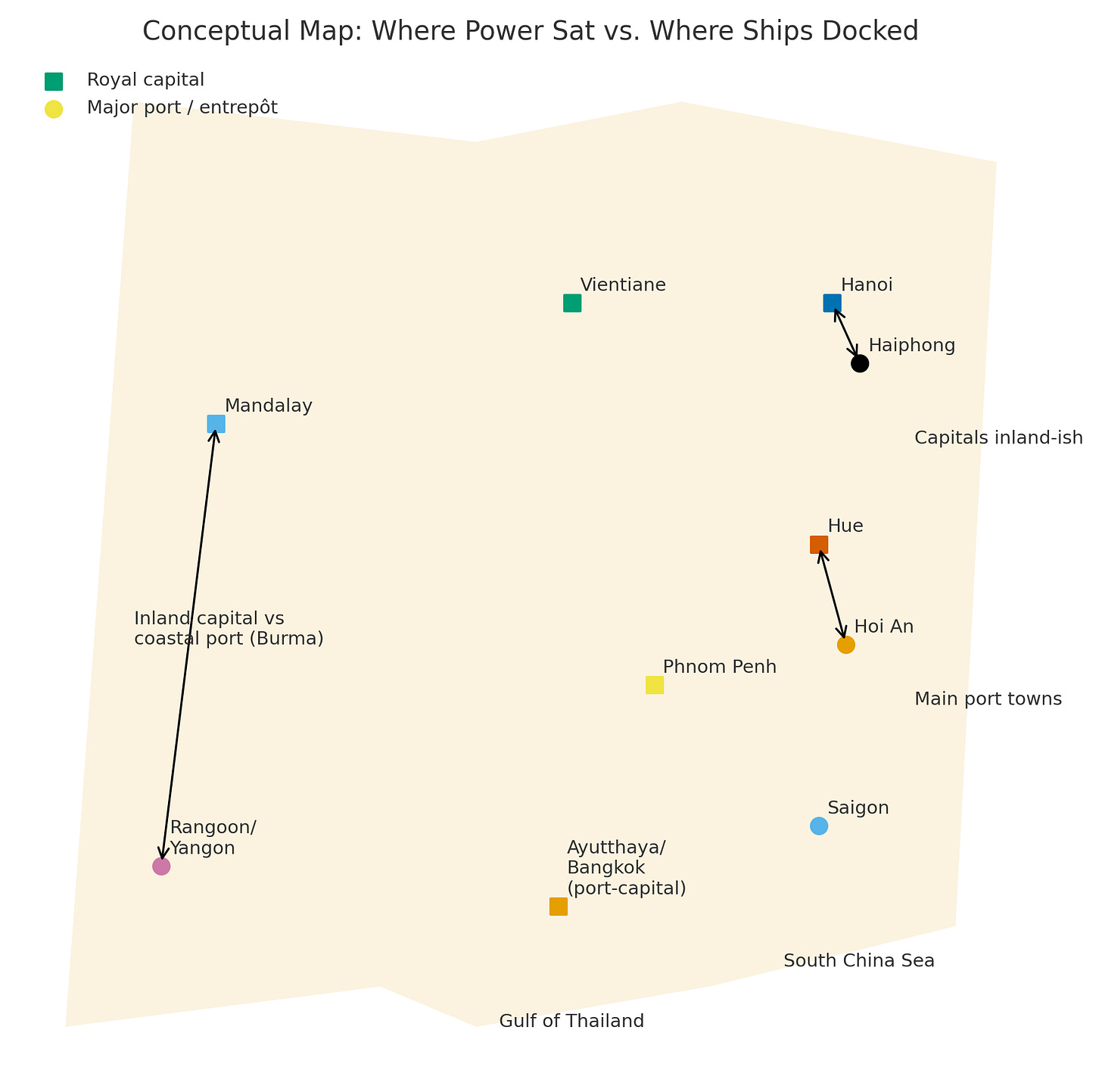

To start, Siam benefited from a quirk of capital geography. Its governing cities—first Ayutthaya and then Bangkok—formed along the busy southern trading ports of the Chao Phraya. This, I speculate, was a major driver of Siam’s relative economic success: the stationing of the kingdom’s elites in capitals defined by trade and foreign interaction facilitated a distinctly open, pro-commerce ruling class centuries before European powers arrived.

The contrast with neighbors is stark. Cambodia’s Mekong–Tonle Sap system was too shallow and seasonal for sustained long-distance trade; Laos was landlocked, with its stretch of the Mekong broken by rapids. Burma had sea access, but its Konbaung capitals—Ava, Amarapura, Mandalay—sat far upriver on the Irrawaddy, while Rangoon and the delta remained peripheral to royal politics.

Vietnam was the closest rival in terms of good harbors, but its court was both physically and ideologically distant from maritime trade: Hanoi and later Huế were ritual-bureaucratic centers, while the main Chinese commercial communities clustered in ports like Hội An and Saigon. Even where the court overlapped with trade hubs, Confucian ideology tended to discourage close social mixing between nobles and merchants.

To sum up: in most of mainland Southeast Asia, the place where ships docked, and the place where power sat, were partly decoupled. Siam was the one where they largely coincided, and that mattered.

Historical evidence aligns with the image of Siam as an unusually open kingdom. Per Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit’s A History of Thailand, European accounts suggest that Ayutthaya was already the largest and most cosmopolitan city in Southeast Asia by the time the Dutch VOC made contact:

In 1621, the Dutch merchant Cornelius Van Neijenrode reported that it surpassed ‘any place in the Indies (except for China) in terms of populace, elephants, gold, gemstones, shipping, commerce, trade and fertility’. Ayutthaya grew into perhaps the largest city in Southeast Asia, and certainly one of its most cosmopolitan. The city was ringed by settlements of Chinese, Viet, Cham, Mon, Portuguese, Arab, Indian, Persian, Japanese, and various Malay communities from the archipelago. The Dutch arrived in 1604, competed for a share in the trade to Japan, and added their settlement to this ring. The French and English followed later in the century. Proverbially the city was said to accommodate ‘forty different nations’.

In turn, the Siamese court was remarkably open to drawing on foreign cultures and expertise:

The court made use of these peoples. It recruited Malays, Indians, Japanese, and Portuguese to serve as palace guards. It brought Chinese and Persians into the official ranks to administer trade. It hired Dutch master artisans to build ships, French and Italian engineers to design fortifications and waterworks, British and Indian officials to serve as provincial governors, and Chinese and Persians as doctors. A Japanese, a Persian, and then a Greek adventurer (Constantin Phaulcon) successively became powerful figures at court. The kings, especially Narai (r. 1656–88), welcomed new knowledge; exchanged embassies with the Netherlands, France, and Persia; and borrowed dress and architectural styles from Persia, Europe, and China.

Far beyond simply adopting foreign customs, noble women often intermarried with merchants, and in Siam, such intermarriage brought outsiders unusually close to the kingdom’s royal core. The best-known case is King Narai’s Greek adviser Constantine Phaulkon, a former trader who married the court lady Maria Guyomar de Pinha and rose to the very top of the administration. This introduced a meritocratic component to Siam’s elite: commercial acumen counted toward who came to intermarry with nobles and shape court culture. It also contrasts starkly with the meritocracy of Confucian societies, where selection effects for intelligence were contaminated by anti-merchant bias.

Tax incentives also mattered for attracting talented migrants. Because Ayutthaya depended so heavily on trade, Siam became unusually reliant on tax farming compared with other mainland kingdoms. The rights to tax a particular industry—opium, liquor, rice milling, ferry tolls, gambling, market fees—were auctioned off to the highest bidder, often foreign merchants. Besides requiring capable would-be administrators, tax farms produced cash-based revenue, in contrast to the corvée labor and land-based assessments that still dominated fiscal systems in Burma, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. When Siam began to modernize in the nineteenth century, such liquidity likely made the process easier.

Because Siam needed tax-farmers and merchants to generate state revenue, it created explicit incentives for immigrant traders. Chinese merchants, for example, were placed outside the corvée-labor nai–phrai system and instead paid a special head tax (the phuk phii). Other kingdoms relied on migrant trading minorities, but Siam went unusually far in actively recruiting such outsiders and allowing them to integrate with the nobility.

Coastal Chinese migrants were the main beneficiaries of this regime. By the eighteenth century, they already dominated much of Siamese commerce, just as their descendants do in modern Thailand.2

Chinese migration to Siam’s Chao Phraya corridor happened steadily over the centuries, as junks from Guangdong and Fujian made regular calls at its southern ports. Thanks to Siam’s desire for foreign talent, many of these migrants settled, trading in rice and textiles or taking up tax farms on opium, liquor, gambling, and other lucrative monopolies.

Catalysts in China and Siam punctuated the flow of Chinese migrants, changing Siam’s demographics drastically. One major wave of Chinese migration came in the early eighteenth century, amidst famine in China:

From the 1720s, Siam exported rice to ease the shortage and famine in southeastern China and was rewarded with trading privileges. Chinese migrated to settle in Siam, with the community estimated at 20,000 by 1735.

Upon arrival, Chinese migrants could rapidly rise to positions of power due to the openness of Siam’s ruling class:

At least two Chinese rose to the post of phrakhlang [minister of trade]. The first, according to French missionaries, ‘placed his Chinese friends in the most important posts... with the result that the Chinese now do all the trade of the kingdom’. Some Chinese married into the court elite. Others traded rice, manufactured noodles, distilled liquor, and raised pigs.

A greater catalyst for Chinese immigration came decades later with a particularly ruinous Burmese invasion. Burma long invaded Siam—forty-four times over a 300-year span by popular Thai accounts—but in 1767 it achieved its greatest assault on the rival kingdom, taking hordes of locals as slaves and destroying the existing capital at Ayutthaya.

With Siam depopulated and fiscally weak, foreign merchants had an even greater opportunity to fill the void. Many Chinese traders, in turn, gravitated to the new capital chosen to replace Ayutthaya: Bangkok.

The dynastic transition only further facilitated this merchant influx. Taksin the Great, the military leader who briefly ruled in the post-Ayutthaya chaos, was himself the son of a Chinese merchant from Guangdong. Short on labor and revenue, he actively encouraged Chinese migration to the new capital by reviving the junk trade with southern China. Under his successors in the early Chakri period, these communities were granted prime riverfront land in Sampheng, the nucleus of Bangkok’s Chinatown today.

The strategy worked. In the decades after the founding of the capital, so many Chinese migrants settled in Bangkok that European observers routinely described it as a Chinese city. Estimates based on late-19th- and early-20th-century census material suggest that people of Chinese descent may have made up a third to half of Bangkok’s inhabitants by the early twentieth century.

Chinese migrants would dominate every major sector of the Bangkok-centered Siamese economy. And as they had done before, successful Chinese arrivals integrated with existing Thai nobles. The French would even weaponize Sino-Thai intermarriage in their racial propaganda, arguing that the Lao were a distinct race, while the Siamese were not, because they had become too intermixed with the Chinese.

These patterns were not confined to the Chinese. Consider the Bunnag family, who show that it was not only the Chinese who gained from Siam’s open elite:

Some became almost as splendid as the ruling family itself, in particular the Bunnag family, whose roots went back to Persian immigrants in the 17th century and whose leading light had been Yotfa’s personal retainer in the Taksin era. In a trend that began before 1767, the provincial areas were divided under three ministries (kalahom, mahatthai, and krom tha), which became virtual sub-states with their own treasuries. The Bunnag controlled at least one and sometimes two of these across four generations. By mid-century, the two Bunnag patriarchs were popularly known by an honorific (ong) formerly applied to royalty.

Such trends persisted into the next century. With the transition to the Chakri Dynasty, Siam, though superficially an absolute monarchy, continued to delegate significant power to commercial families and administrators:

While Yotfa was very active in Bangkok’s revival, his successor, Loetla (Rama II), withdrew into a ritual role and left administration to the great nobles. Nangklao (Rama III) was active as both king and merchant, but Mongkut (Rama IV) again ceded power to the nobles, complaining occasionally how few attended either his council sessions or major royal rituals. Every succession in the 19th century was tense to a greater or lesser degree because of the possibility of another dynastic shift, as had occurred in 1767 and 1782. Approaching the last of these transitions, Mongkut worried that ‘general people both native and foreigners here seem to have less pleasure on me and my descendants than their pleasure and hope on another amiable family’.

Siam was unique among its neighbours for its commercial bent, but it was still regarded as legally backward in the eyes of Western powers. This is where the Chakri dynasty’s adaptiveness was paramount. In the mid-nineteenth century, Rama III and then Rama IV expanded Siam’s relations with Britain, the United States, and other Western powers, culminating in the Bowring Treaty of 1855 under Mongkut (Rama IV). We cannot know exactly why they were more willing to engage with and emulate Western nations than neighboring monarchs, but the weight of commercial families in Bangkok politics made such recourse more likely, even if individual kings had misgivings. It is worth remembering, too, that the Chakri Dynasty itself was quite mixed with outsiders. Rama III, who had a strong personal interest in commerce, was the son of Sri Sulalai, a consort of Persian Muslim descent who entered the Buddhist court. In the context of such a cosmopolitan elite, reflexive distrust of the outside world was not the norm.

Whatever the reason, Siam’s royals showed an uncanny ability to diagnose their vulnerabilities with respect to the encroaching European powers:

Within the elite, there was debate on what reforms were needed to manage the threat of European colonialism. In 1884, as the French took Indochina and the British fought their way into Upper Burma, Chulalongkorn asked Prince Prisdang, his cousin at the head of the Paris legation, how Siam’s independence could be preserved. Three other half-brothers of Chulalongkorn in Europe at the time were among the 11 signatories of the reply, sent in January 1885. The danger to Siam, they argued, arose from the west’s belief in its own mission to bring progress and its right to seize a country that failed to provide progress, justice, free trade, and protection for foreign nationals. They advised,

There is only one way which is to govern the European way . . . To avoid the threat, we must earn mutual respect . . . But the government of Siam at present is the opposite of Europe, lacking the law called a constitution, which represents the wisdom and power of all the people, and they think brings justice . . . At present the Europeans report . . . that the only person who governs in Siam is the king, helped by his brother, Prince Devawongse . . . no country in Europe will believe there is justice in Siam.

Reformers consciously modeled their efforts on those of Meiji Japan. But a deeper reading of this is that Siam’s court was doing what it had already done centuries prior: integrate foreign knowledge.

Still, Siam’s monarchical tradition precluded forays into parliamentary-style representation. Instead, the monarchy refashioned itself as a progressive vehicle:

In the past, the king had provided protection that allowed the people to pursue the Buddhist path towards nibbana. Now, the king’s role was to bring progress. Both Mongkut and Chulalongkorn had travelled round the country like monks on thudong (pilgrimage) to know the people’s problems. All the king’s actions were devoted to improving the people’s well-being. ‘The Thai way of government is like a father over a son, as is called in English paternal government.’

Thailand stands out from its neighbors for a kind of quirk of geography and history: an unusually open, fluid nobility gradually produced a commercially adept Sino-Thai ruling class that enabled swift modernization. Without a merchant influx, Siam probably would have remained too agrarian to withstand colonization, as was the case with Burma, Laos, and Vietnam.

Does this history explain Thailand’s current level of development? Probably. The businesses that contribute most to the Thai economy today are still run by ethnic Chinese families. That is what economists like Garrett Jones and Gregory Clark would predict: long-run development tracks with where commercially skilled populations clustered centuries ago.

As a side note, it is remarkable how well Chinese migrants integrated with native Thais. Unlike in much of Latin America, there does not seem to be a visible caste system today. Unlike in Malaysia, there are fewer grievances about Chinese economic dominance.3 The integration was so smooth that it is easy to miss how important Chinese people were to Thailand’s development.

Vietnam is not a majority-Buddhist nation, but I am including it anyway.

Per Wikipedia, 50 Thai business families of Chinese ancestry control approximately four-fifths of the economy’s total market capitalization. There are a bunch of citations for this that I cannot check.

Historically, this is somewhat of an overstatement. The less open-minded King Rama VI called the Chinese “the Jews of the East” in a 1914 essay.

Interesting topic

Thai-chinese ???